Over the years, the United States has produced many remarkable generals and admirals, but only a few have stood out as world-class strategists and leaders of troops. As Veterans Day approaches on November 11, let’s remember and celebrate them. Here is my list of America’s finest 11 commanders.

William Tecumseh Sherman, 1820 – 1891 (Civil War)

On the eve of the Civil War, William Tecumseh Sherman wrote to a friend in the South: “This country will be drenched in blood and God only knows how it will end. You people speak so lightly of war. You don’t know what you’re talking about. War is a terrible thing.”

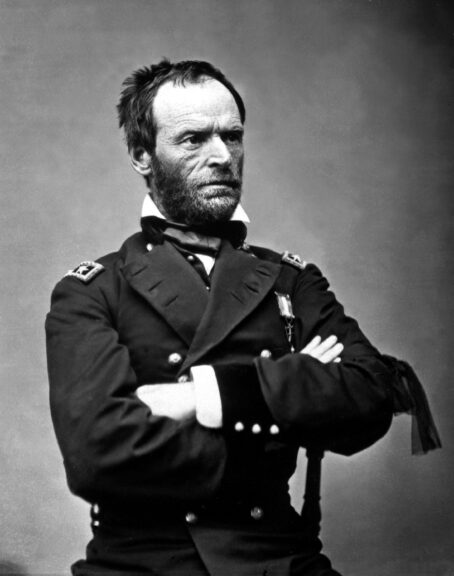

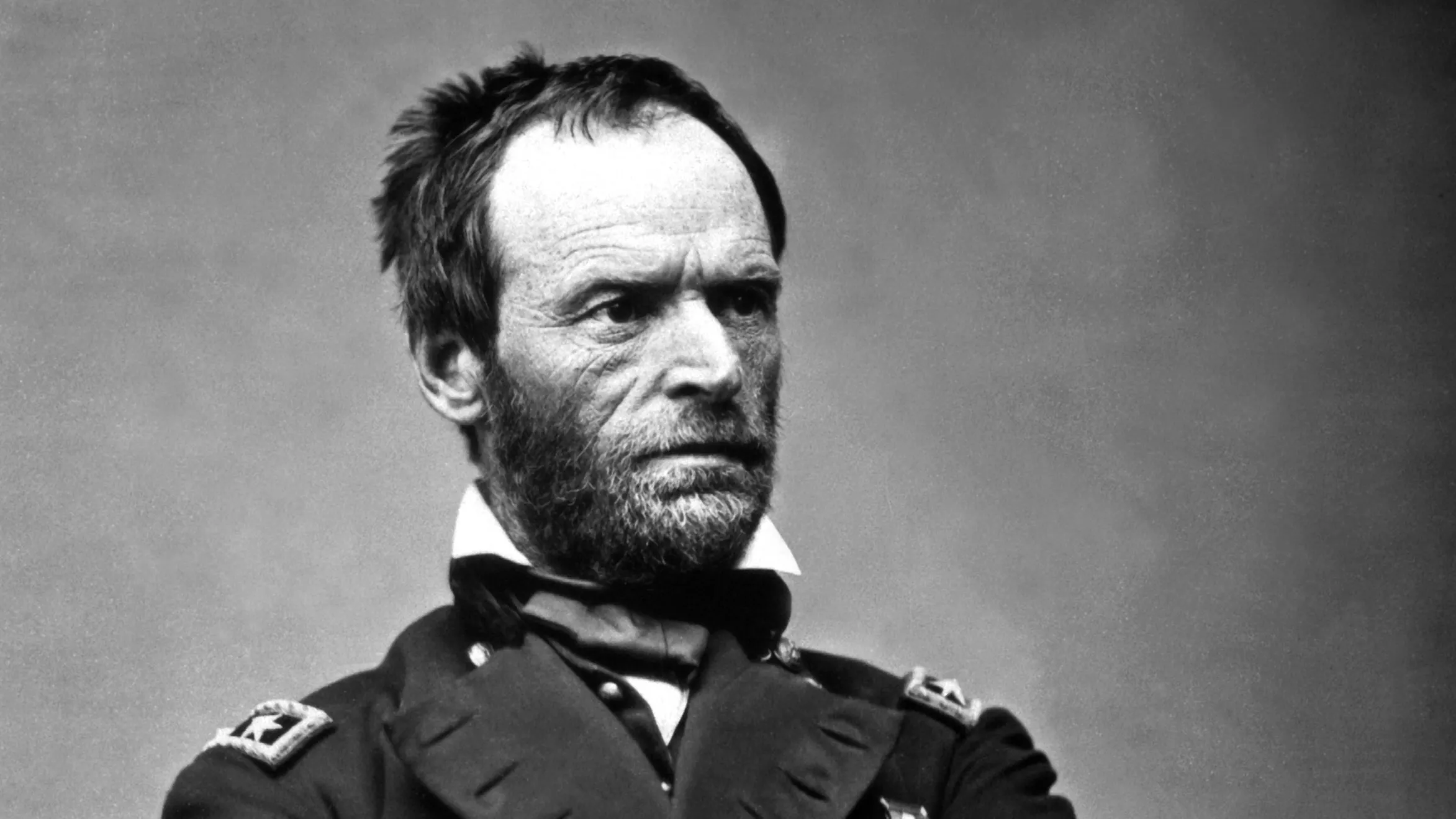

Gen. William T. Sherman, ca. 1864-65. Mathew Brady Collection. (Army). WAR & CONFLICT BOOK. Wiki Commons.

Such language prompts some to remember the grizzled, steely-eyed Sherman as an Old Testament-like prophet of modern war and all its desolations. And with good reason. He is associated with the destruction of Georgia in his “March To The Sea” and then up through the Carolinas. In doing so, Sherman tore the guts out of the Confederate war machine and in many ways ushered in the modern age of conflict. But, unlike his superior Grant, who ended up bogged down for months in a grisly stalemate with Lee’s army in Virginia, his war was waged on factories, plantations, railroads, and fertile farmlands as much as the enemy’s legions. Sherman understood that the materiel production of the South was essential to maintaining the Confederate War effort in the field. And no other commander destroyed the Southern infrastructure with more ruthless efficiency than he.

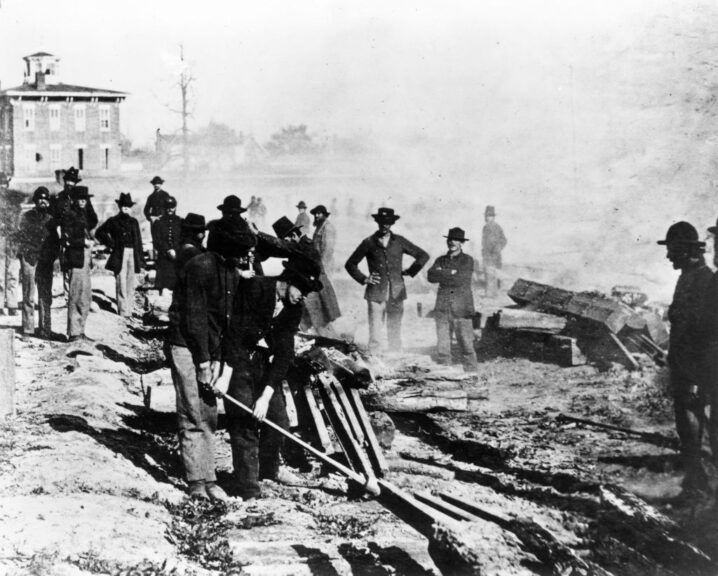

Gen. William T. Sherman & staff. (Photo by Matthew Brady/Buyenlarge/Getty Images)

When Grant was promoted to overall General-in-Chief of the Union war effort, he showed his confidence in Sherman by naming him as his replacement as head of the Division of the Mississippi with its three western armies. It was a smart decision, although not without concern by others at the time. In early 1862 Sherman suffered a nervous breakdown, and his performance was not always consistent. But Grant saw something in his fellow native Ohioan. Sherman, in turn, would be Grant’s most faithful subordinate. “Grant stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by Grant when he was drunk, and now we stand by each other.”

The loyalty flowed down through the ranks as well. The men loved “Uncle Billy” precisely because they knew he would not waste their lives in fruitless frontal attacks. A more rugged lot than their spit-and-polish eastern counterparts, his men were mostly from the Western states of Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Michigan, Ohio, Iowa and Minnesota. They wore broad-brimmed hats rather than the more iconic cap, and the officers not very distinguishable from the rankers, who called themselves Sherman’s “bummers”.

1864: General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820 – 1891) and members of his staff before the siege of Atlanta, Georgia. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Loyalty aside, William Sherman turned out to be arguably the most foresighted, even ingenious, of all 19th Century military commanders. Having experienced the horrors of war from 1861 at First Bull Run, through Shiloh in 1862, and then again in 1863 at Vicksburg and Chattanooga, by 1864 as he embarked on his invasion of Georgia, Sherman vowed not to waste his men’s lives in foolish frontal assaults, ironically even as his friend Grant was doing just that in Virginia.

Instead, tasked by Grant with taking Atlanta, Sherman would engage in a war of constant maneuver against his very capable Confederate opponent, Gen. Joe Johnston, and repeatedly flank, march, flank, and march his way south through Georgia until he had Atlanta cut off. Only once during his relentless 110-mile advance south towards the city, at Kennesaw Mountain, did Sherman lose his patience and attempt a frontal attack, suffering severe if predictable losses. He never tried such a foolish tactic again.

Illustration of Union troops advancing during the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, June 27, 1864. Northern General William Tecumseh Sherman launched a frontal attack on Southern General Joseph E. Johnston’s well-prepared Confederate forces and suffered a rare defeat in his campaign to Atlanta. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

After Johnston’s replacement, the fiery but impetuous John Bell Hood, took command of the Confederate army, the brash rebel general attacked the more powerful Sherman, who was thrilled to see the rebs come out and fight in the open in a pitched battle against his experienced Westerners. Hood’s offensive was repulsed outside the city after a series of violent engagements. With the defense of the city now untenable, Hood abandoned the heavily damaged Atlanta to the Yankees. A triumphant Sherman marched into the South’s second most important urban center in September 1864, telegraphing to Lincoln: “So Atlanta is ours and fairly won.”

After losing Atlanta, Hood marched north to Tennessee, taking aim at the tenuous Union lines of communication, in the hopes that Sherman might follow him. But the confident Sherman dispatched a force under the command of rock-steady Gens. George Thomas and John Schofield to pursue Hood. Some criticized Sherman for letting Hood’s army go, but he had complete faith in his subordinates and their contingent of motivated Yankees to handle any threat the Confederates may have posed farther north. Sherman went so far as to say he would “give [Hood] his rations” to go in that direction, as “my business is down south.” As it turned out, Thomas eventually routed the brave but impulsive Hood outside Nashville in December 1864.

General William T Sherman’s army leave Atlanta on its ‘March to the Sea’. Sherman’s men destroy the South’s capacity to wage war by killing southern livestock, burning crops and tearing up southern railroads. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Part of the reason the Confederate threat to his rear was of little concern to Sherman was that he’d planned on abandoning his lines of communication to march south out of Atlanta to the sea. Writing to Grant he quipped: “If you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic, I think ol’ Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks.”

Indeed, Sherman’s whole life seemed to be a preparation for his moment of destiny in Georgia. After resigning his commission in 1853, the West Pointer held many jobs from banker, farmer, and lawyer to college administrator, businessman, and trader. He’d also seen much of this very part of the country while in the army. All this real-world experience made the highly intelligent and adaptable Sherman a master of logistics. And as such, he decided to march through Georgia without having to shed men to defend vulnerable rail lines in his rear…thus his 100,000-man army would have to live off the land. Sherman studied tables and schedules, he calculated harvest yields when planning his routes, and managed to catalogue other materiel he expected to find in each county and each town along his path and concluded, “I can make the march, and make Georgia howl.”

And that is what he did. Severing communications and systematically wiping out Georgia’s ability to feed and supply the South’s armies, from mid-November to December 1864, Sherman’s troops cut a 250-mile long by 30-mile wide swath of destruction through the South’s breadbasket. No one in the North really knew where he’d disappeared to until he marched up in Savannah and offered the city to Lincoln as a “Christmas present.” But he was not finished. He then turned his army north and marched through the Carolinas, once again destroying anything of military value in his path and defeating his old nemesis, the re-instated Joe Johnston, and what was left of the Southern army in this region in 1865. Columbia, South Carolina, where secession all began, fell in February 1865. Johnston surrendered to Sherman on April 26, 1865.

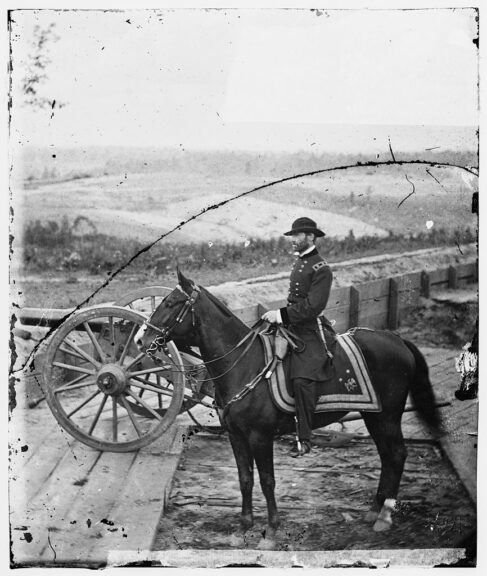

ATLANTA, GA – 1864: In this image from the U.S. Library of Congress, U.S. Gen. William T. Sherman sits on horseback at Federal Fort No. 7 September-November, 1864 in Atlanta, Georgia. (Photo by George N. Barnard/U.S. Library of Congress via Getty Images)

Sherman’s capture of Atlanta and subsequent march through Georgia and the Carolinas left two different legacies. First, it is no exaggeration to say that with war weariness in the North and Grant’s having shattered the Army of the Potomac against Lee’s defenses in Richmond, Sherman’s relatively bloodless victories saved Lincoln’s campaign, and thus the United States as we know it. It also left a bitter taste in the South and, though actually feted by Atlantans soon after the war, became a villain in the revisionist Lost Cause narrative, including grossly exaggerated claims that his men raped, pillaged, and murdered their way south as would a band of rampaging Vikings. But the record shows that Sherman killed far less Southerners than did Lee or Hood. And that his rage was targeted towards the plantation class, whom he blamed for waging the war with the sons of poor parents.

As far as the Southern gentry was concerned, however, Sherman’s cardinal sin was to wage war on property. Sherman understood the unavoidable nexus between civilian labor and the capabilities of their armies in the field. An unheard-of approach in a supposedly more genteel age where civilians and armies were considered separate and distinct. As Machiavelli said: “Men sooner forget the death of their father than the loss of their patrimony.” And although seen as the precursor to strategic bombing, Sherman was far less indiscriminate in his killing — and few civilians died from outright Union atrocity during his operations.

It is hard to argue against the notion that Sherman’s campaigns not only saved the Union by saving Lincoln’s presidency, but saved tens of thousands of lives on both sides by advancing the South’s inevitable collapse and defeat by at least six months to a year. For a man whom embittered Southerners may still claim has blood on his hands, certainly many of these critics today can trace their lineage back to defeated men in gray who nevertheless came home on foot or horseback rather than in a pine box courtesy of Uncle Billy’s ruthlessness and clarity of vision.

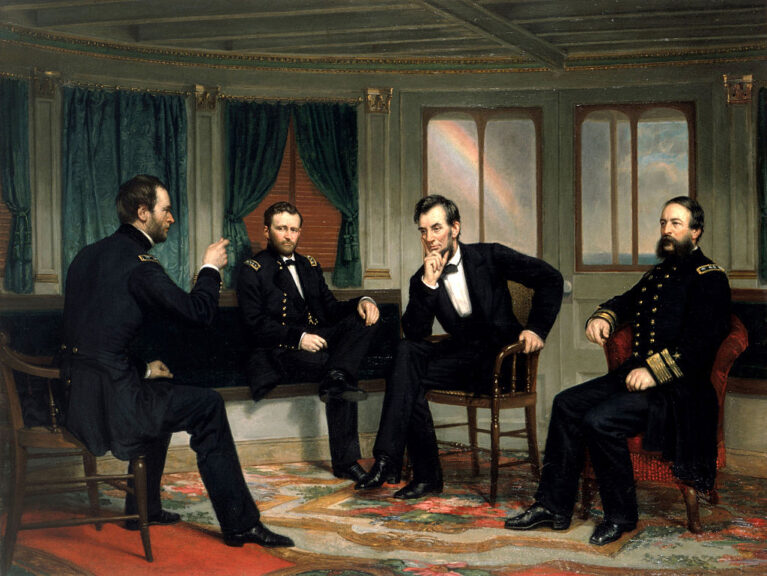

Circa 1868, oil on canvas, 119.7 x 159.1 cm (47.13 x 62.64 in). Located in the White House, Washington, DC, USA. Sherman, Grant, Lincoln, and Porter aboard the River Queen on March 27th & March 28th, 1865. (Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Sherman died of pneumonia in 1891. His funeral in New York was held during a blustery rainswept winter day. One of his pall-bearers was none other than his respected adversary Joe Johnston. Out of respect for an old comrade and foe, the 84-year-old Johnston refused to wear a hat. When a friend worried he might get sick, Johnston waved him off, “If I were in [Sherman’s] place, and he were standing in mine, he would not wear a hat.” Johnston died of pneumonia a month later.

* * *

America’s Top 11 Generals

RELATED: #6 Admiral Chester Nimitz

RELATED: #5 Thomas ‘Stonewall’ Jackson

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities trader, columnist, and author of two acclaimed novels. His newest book, the fact-based LIFE IN THE PITS: My Time as a Trader on the Rough-and-Tumble Exchange Floors will be published in December and is currently available for pre-order. You can also find more of Brad’s articles on Substack.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)