Over the years, the United States has produced many remarkable generals and admirals, but only a few have stood out as world-class strategists and leaders of troops. As Veterans Day approaches on November 11, let’s remember and celebrate them. Here is my list of America’s finest 11 commanders.

This series is about military prowess and those who excelled on the battlefield. The inclusion of any Confederates in this list should not be misconstrued as in any way supporting the cause of the self-described Slave-Holding Confederacy itself for which such men fought. The preservation of the monstrous injustice of slavery in North America and the stated goal of the seceding states had to be destroyed. But this does not diminish the achievements of certain Southern generals on the field of battle, which is solely what this series seeks to examine.

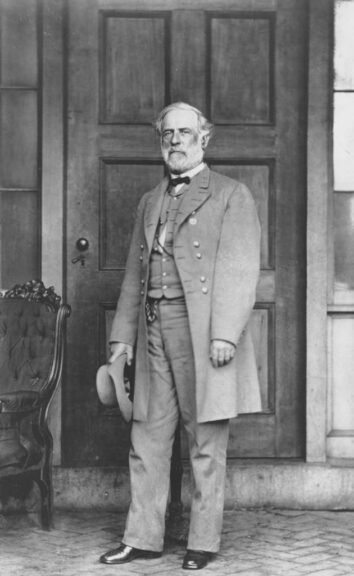

Robert E. Lee, 1807 – 1870 (Civil War)

An officer who served with Lee once said of him: “His name might be audacity. He will take more desperate chances and take them quicker than any other general in this country, North or South.” This was an apt description of the man the Northerners came to know as “The Gray Fox.” Yes, Lee was fighting against the U.S. and not for it. However, he was still very much the product of the American military tradition, and it would be remiss to not include him for brilliance as a battlefield commander, even if his choice of political causes was disastrous. The fact is, Lee, as the historian Shelby Foote noted: “Is a great general on both the offense and the defense.” And few commanders have managed to fight so long and effectively while being so out-manned, out-gunned, out-fed, and out-supplied as Lee.

American Confederate Army general Robert E Lee (1807 – 1870), Richmond, Virginia, 16th April 1865. (Photo by Mathew Brady/FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

At the outset of the Civil War, Robert E. Lee was America’s most prominent soldier. Son of the Revolutionary War hero “Light Horse Harry” Lee, he was from one of the first families of Virginia. Having turned down Lincoln’s offer to command the Union Army, Lee would end up taking over the premiere Confederate Army being pressed back against the capital of Richmond in June 1862 after Gen. Joe Johnston was wounded. Within two months Lee counterattacked Union general George McClellan’s advancing Yankees at the brutal Battle of the Seven Days on the outskirts of the city and sent him sailing back to Washington D.C., saving the rebel capital.

Then, while one Union army was effectively off the chessboard in transit, Lee pivoted north to face another threat. In a masterful campaign, he marched his army up northern Virginia to intercept, out-maneuver, and defeat a second Union army under Gen. John Pope at 2nd Bull Run (August 1862). In the three months he’d been in command, Lee had rescued the Southern capital, defeated two different armies while inflicting some 30,000 Union casualties, and cleared the entire state of Virginia of enemy troops. It was a remarkable turn of fortune that put the North on notice that a clever and dangerous foe was now in command of the South’s principal army.

An illustration of Thomas Stonewall Jackson at the Battle of Bull Run, during the US civil war, circa 1863. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Although his vaunted Army of Northern Virginia was exhausted, ill-fed, and clothed from a poor supply chain and constant marching and fighting, Lee nevertheless gambled on an invasion of Maryland. Believing a Confederate victory on Union soil would convince Great Britain and France to form an alliance, his hopes were dashed when McClellan and his 87,000-man Army Of The Potomac, back from the peninsula and now infused with the remnants of Pope’s army, stopped him along the banks of the Antietam Creek in September 1862. In the bloodiest single day in U.S. history, Lee showed tactical brilliance in the field by holding off repeated attacks by a determined Union army twice his size, fighting McClellan to a stalemate. Nevertheless, Lee retired back into Virginia to recoup his losses and await the North’s next move.

In December 1862 a new Union commander, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, attempted to cross the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg and march on Richmond. Lee was waiting and delivered the most one-sided victory of his command, laying waste to 12,000 Union troops with little loss of his own.

Burnside, like Pope and McClellan before him, was relieved of command and a new, confident Gen. Joe Hooker was next up as head of the Army Of The Potomac. This time Hooker surprised the Confederates with a well-conceived pincer attack, crossing the Rappahannock at several points to fall on both Lee’s flanks at Fredericksburg on the Confederate right and the Wilderness, a dense woods, on the left. Hooker confidently predicted that in the face of this squeezing attack, Lee would be compelled to either retreat or be destroyed in a pitch battle against overwhelming odds. Instead, the unperturbed rebel commander responded to Hooker’s boldness in kind and out-flanked the flanker. At the Battle of Chancellorsville (considered a military masterpiece) Lee divided his inferior army and took an enormous chance by sending half of it under his indomitable corps commander Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson to hit Hooker seven miles to the west on his exposed flank amidst the impenetrable Wilderness. The attack was a complete surprise and rolled up the Union Army’s shattered flank. Hooker, like the preceding generals who’d attempted to outfox the fox, retreated.

1863: The Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

Though bloody (Lee suffered 25% casualties) his stunning victory at Chancellorsville prompted Lee to head north again. This time, however, he faced an Army Of The Potomac now being led by the competent and cool George Meade. In July 1863, during a three-day struggle around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Lee was dealt his worst loss of the war, losing some 27,000 out of the 75,000 men he brought north. He retreated back into Virginia, never to go on “the aggressive” as he called it again.

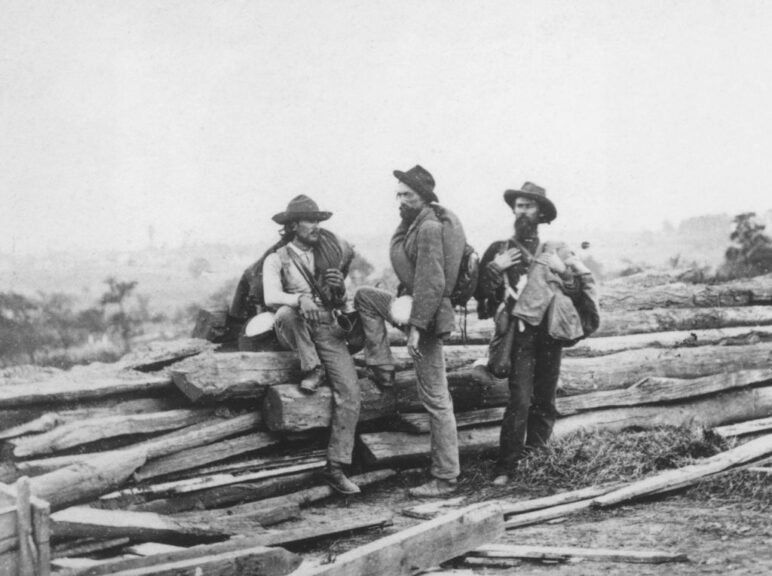

Confederate prisoners at Seminary ridge during the battle of Gettysburg in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania circa July,1863. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

By the summer of 1864, with no hope of foreign intervention, and lacking the strength for any more offensive actions in the face of an overwhelming Union superiority in manpower and industry, Lee would grapple with U.S. Grant, his final and most formidable foe. The two gifted commanders fought a series of brutal engagements across the Virginia countryside from The Wilderness and Spotsylvania (May 1864) to Cold Harbor (June 1864) and finally settling in for a siege at Petersburg that would last nine months. Although weakened, Lee saw that his situation was not so hopeless as it appeared. He’d effectively halted Grant’s thrust towards Richmond and now the two armies were at loggerheads southeast of the capital at Petersburg. And Lee had managed to inflict over 50,000 casualties on his Northern enemy.

Understanding that wars are political as well as military, General Lee realized that with the 1864 elections approaching, the high casualties the war weary North was suffering at his hands might be enough to vote out Lincoln and prompt a more pro-South Democrat administration which might welcome the rebellious states back into the Union, or even let the South go its own way. But due to the actions of another Union commander further up our list, this political upheaval did not come to pass. When Lincoln handily won re-election in November 1864, the South was doomed. A tired but resplendently-uniformed Robert E. Lee surrendered what remained of the surrounded Army of Northern Virginia to the mud-splattered Grant in April 1865.

Vintage illustration at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia depicts Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendering his 28,000 troops to Union General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the American Civil War. Keith Lance. Getty Images.

Lee went on to head Washington College (later renamed Washington And Lee) and died in 1870 of a chronic heart ailment.

Robert E. Lee has been called a “marble man” for his stoicism and almost impenetrable personality; following the Civil War, he was idolized in the South to the point of being a demigod. But, Lee was just a man, like any other, and as such showed flaws…some of which could be quite detrimental to his cause. Most damning was his tendency to be profligate with his men’s lives. Indeed, the historian James McPherson calculated that Lee suffered the highest casualties as a percent of those under his command than any other army commander of the war, North or South. Lee’s confidence in the almost superhuman capacity of his troops to overcome all odds prompted him to send them into suicidal charges against well-prepared Union positions at Malvern Hill (June 1862) and again at Gettysburg a year later. It was, in fact, a very dangerous business fighting for “Marse Robert”.

Still, his men adored him. One man in the ranks declared, “I would charge hell itself for that old man!” So commanding a martial figure did Lee cut that once when the Confederates were marching through a Pennsylvania town, a brave loyal Union woman was brazenly waving the American flag before them. Then Lee rode up to her and looked down from his white horse Traveller. She dropped the flag, clasped her hands together and said of Lee: “Oh how I wish he were ours!”

Although Lee fought for an unjust cause in the preservation of slavery — one that had to be destroyed — there is no doubt that his campaigns will be studied in military academies as long as such institutions exist.

* * *

America’s Top 11 Generals

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities trader, columnist, and author of two acclaimed novels. His newest book, the fact-based LIFE IN THE PITS: My Time as a Trader on the Rough-and-Tumble Exchange Floors will be published in December and is currently available for pre-order. You can also find more of Brad’s articles on Substack.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)