The following is an edited transcript of an interview between Daily Wire editor-in-chief John Bickley and Mike Rowe on a Saturday Extra edition of Morning Wire.

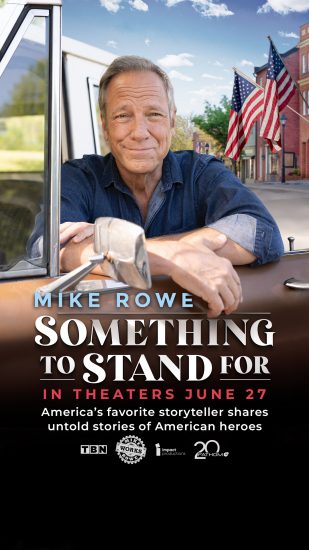

Mike Rowe became a national name as host of the massively popular reality show “Dirty Jobs,” in which he traveled around the country – and got his hands literally dirty – learning what hard-working Americans do daily to make a living. He has since gone on to head up the nonprofit MikeRoweWORKS, which has awarded millions in “Work Ethic” scholarships – and he’s produced more widely popular content. Mike’s latest labor of love is a feature-length film “Something to Stand For,” part documentary/part narrative that’s soon to release in theaters. He believes America is not just hungry but starving for something to unite around.

JOHN: Joining us now to discuss his new movie, “Something to Stand For,” and what’s driving it is Mike Rowe. Mike, thanks for coming on.

MIKE: Thanks for having me.

JOHN: It’s wonderful to have you here in-studio, the first time you’ve been here with us. I watched your film, and I have to say, I got a little teared up at times, I laughed a lot, but I came away thinking you present it as something that’s going to unite the country. What strikes me about it is the tone. There is not a hint of cynicism in this film. So maybe we could start by talking about the big picture. What was your vision for the film and why do you think it’s so needed at this time?

MIKE: Well, first of all, with regard to cynicism, I’ll say it like this. I wrote a book a few years ago, and the epigram was from John D. MacDonald and his series of books about Travis McGee, this is a fictitious character upon whom most of my business model has been based, weirdly enough. But, among many quotable things, McGee said, “I am wary of a great many things in this life, but above all, I am wary of all earnestness.” For a long time, that kind of informed my worldview. You know, in the ‘80s and ‘90s we had shows coming along that were always ironic and always kind of cynical about this, that, or the other. And with 20 years of “Dirty Jobs,” I always had my tongue in my cheek and I was always open to the idea that we were going to debunk something. Now, I feel like we turned some kind of corner and we’ve left the age of irony and things are brittle and people are looking for something they can trust, because that trust in traditional institutions has eroded. So, there is an opportunity, I think, to be earnest in spite of McGee’s warnings. I think there’s an opportunity to embrace a certain kind of sentimentality. You can’t do it unctuously, it needs to be honest or at least personal. And so that’s what the movie is. It’s nine stories that I wrote over the years in the style of Paul Harvey’s, “The Rest Of The Story.” And because they’re all patriotic in nature, I thought stitching them together with a field trip of sorts to D.C. might be a fun way to look at history, and mystery, and current events, and storytelling, and just kind of smear it all together into a boolean base of, well, why not? It’s Independence Day.

Copyright 2024 TBN. Trinity Broadcasting Network. All Rights Reserved.

JOHN: To give us a sense of what the film is, you said there are nine stories, sort of vignettes. There’s a mystery element to each of them. Can you explain the narrative approach to each of the stories?

MIKE: Look, there are no new ideas. I would love to tell you that I’ve stumbled across some new way to tell a tale. Paul Harvey, Jr. and Paul Harvey mastered this in the late ‘70s and throughout the ‘80s with “The Rest Of The Story,” where, essentially over maybe eight minutes, you learn something you didn’t know about somebody you do. So they would just tell stories of famous people from the inside out. And I loved that format. I can still remember the transistor radio up in the woodpile where my dad and my grandfather and I were chopping wood. Our house was heated by wood stoves and Paul Harvey was always on that radio telling us stories. I remember writing about missing a flight in my book a few years ago. I was driving to BWI and I was in long-term parking. I was running late and just before I got out of the car Paul Harvey comes on with one of his tales. I have to stay, I can’t leave, man. I have to sit there and wait for him to say, “…and now you know the rest of the story.” And I missed my flight. So that kind of storytelling — brief mysteries for the curious mind with a short attention span. That interested me. So what came out the other end was a podcast with about 250 stories in it called “The Way I Heard It.” That turned into a TV show that I didn’t think anybody would watch, but I was wrong. We did six seasons. And now we’re looking at how to adapt these things to the big screen. And the first and most obvious thing to do was to try and make a good natured case for things that are literally and figuratively worth standing for. I didn’t write it for Liberals or Conservatives or Republicans or Democrats. I wrote it for people who still see themselves first and foremost as Americans. In that regard, it’s not a political film by any stretch, but it is unapologetically patriotic. And that might create for some a measure of cognitive dissonance — and that’s just too bad.

LISTEN: Hear the full interview with Mike Rowe on Morning Wire

JOHN: That is too bad. There’s quite a few stories about veterans, heroes from wars. There’s also some stories about people taking some of our great monuments and vandalizing them. It’s a touchy subject. You chose to highlight that now. Why?

MIKE: Well, I’ve been fortunate over the years, on a couple of occasions, where the headlines catch up to whatever it is I’m involved in and makes it relevant in ways that I didn’t really anticipate. It happened with “Dirty Jobs” when our country recessed back in 2009. And all of a sudden we were desperate to have a conversation about the definition of a good job. I just happened to be a guy on the TV and people were asking my opinions and, well, I shared them. Same thing with my foundation. Today, and to your point, we saw the craziness in Lafayette Square. We’ve been reading about it for the last couple of years and, and struggling as a people to try and get our heads around the fact that two things can be true at the same time. We’ve always known that the right to burn the flag has to exist in order for the flag to mean anything at all. We get that. But it feels like if you’re going to do that, you really need to be able to explain why you’re doing it. And the thing that rankled me was that I’m not hearing cogent explanations for the vandalism, for the defacement, for the rage. I’m open to it, but I haven’t heard it. I didn’t really write the movie for those people, but I did write it because of them. Because I think the fat part of the bat, most of us 330 million people, no matter how we vote, still know in our bones that something extraordinary happened, giving us the right to deface our statuary and burn the flag and do all of these other things. And so we owe it to ourselves and to our forebears to at least understand what price was paid. And, to your point, it’s not just about our founding fathers, it’s not just famous people, who we kind of look back at through the mists of time. It’s the 13 guys who died during the Afghan withdrawal. It’s any man or woman who ever wore a uniform, whoever raised their hand, whoever took an oath and whoever meant it. Surely we can stand for them.

JOHN: It strikes me that the way you piece together these stories of famous figures from our past, you’re creating little mini-monuments to some of these folks and highlighting the fact that they are flawed. I’d love to hear one or two of those stories you decided to tell. For example, the Jack Lucas story got me. Tell us about some of those flawed figures that are ultimately worth celebrating.

MIKE: Well, spoiler alert. You know this will wreck the mysteries for a couple of these stories, but I’m happy to do it. I also want to say before I do that when you build a monument to a thing, it can be very tangible. I mean, you can literally be a sculptor. You can literally physically create a work of art for that purpose. You guys do it every day, depending on who you point your microphones at. And I did it for a long time on “”Dirty Jobs,” depending on who we pointed our cameras at. That’s the modern state of statuary. We get to decide what we want to elevate by what we share and, obviously, by the stories that we tell. Jack Lucas was a guy who I read about when I was a kid. The short version is, like a lot of people, after Pearl Harbor, he enlisted to fight for his country and he wound up in Hawaii. He then wound up on an Aircraft Carrier headed to Iwo Jima and then it was discovered that he was a deserter. He was called in to basically be court martialed on the ship. The Captain’s there, he’s livid. What did this guy do? What was his crime? What led him to desert his post? Well, the story essentially reveals that, when he enlisted, he lied. He lied to his mother, he lied to his family, he lied to his enlistment officer. He lied to everybody. He lied because he was 14. And he got stationed in spite of that, and he kept up the ruse, and then he stowed away, he left his post to get on the carrier, to go to Iwo (frickin’) Jima. Into hell. And, by that point, I think he was maybe 16. And what he said to his commanding officer persuaded him and the officer let him fight. What he did on Iwo Jima — I won’t spoil it — but what he did turned him into the youngest person ever to win the Medal of Honor. So that story is not entirely new, but when I’m looking around for things that the most strident opponents might be able to agree upon, surely we can look at Jack Lucas and say, “Alright, that’s something.” In 1998, 70% of Americans described themselves as “intensely to extremely” patriotic. That number today is 39%. And for under 35 years-old, that number is closer to 18 or 19%. So Jack Lucas would not recognize these times.

JOHN: About this younger generation, a culture is created by the stories that are shared, right? And you’re a storyteller. There’s great power in recognizing, first of all, the role that storytellers play and the responsibility they have to tell the stories that matter. When you went through the stories that you chose for this film — and the stories that you’ve chosen for your podcast or for “Dirty Jobs” — what was the process like for you in terms of weeding out what to point the camera toward versus taking a pass? Has that been a complicated process? Is it usually pretty obvious to you?

MIKE: Well, it’s not complicated, but it’s ephemeral and it’s always very fluid in the same way the times are fluid. Going back to that “earnestness” beat, I’ve always been wary of it, because that’s the quality that allows soap salesmen to succeed; it’s the quality that allows news anchors to be believed even when they’re dead wrong; and narrators to be believed. “Listen to how certain I sound when I tell you there are two trillion galaxies,” which I said on a show called “How the Universe Works,” — only to go in two weeks later to tell you that, in fact, It’s only a hundred million. So I’m basically off by two trillion. And I sound the same, by the way. The point is, when I’m off by two trillion I sound just as sure of myself as when I’m not right. And so being surrounded by all of that certain noise and knowing that earnestness is a part of that. Yeah, man, it informed every single thing I did all the way up to the title, not of the film, but of the podcast that the stories were pulled from. It’s called “The Way I Heard It.” And that title was my rejoinder to Paul Harvey’s, “The Rest Of The Story.” I didn’t want to just shamelessly steal it from him, but I wanted to update it. So, I asked myself in 2015, 2016, what’s really emblematic? Like right now, what should the disclaimer be at the end of the news, for instance? Walter Cronkite used to say, “…And that’s the way it is, August 12th, 1972.” Well, you know something, that’s not the way it is in 2024. In 2024, it’s, “That’s the way I heard it.” You may have heard it differently. In fact, I’m pretty sure you have. In fact, If you want to prove it, I’m pretty sure you can reach for your device, do a quick search, and find half a dozen experts who agree with you. And I’ll find the experts who agree with me. Maybe sometimes these experts are historians, maybe sometimes they’re scientists, and maybe sometimes they’re politicians, or journalists, or members of whatever institutions are now currently at all-time low trust levels. Right? And so, that’s kind of a long way of saying it. I wanted to balance the earnestness of my own interest in the topic with something that looks like humility. I wanted to say I could be wrong. Probably am. I wasn’t in the room when Lincoln signed the “Emancipation Proclamation.” I wasn’t there when Jefferson wrote the “Declaration of Independence.” I wasn’t there when Reagan said, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” But I’ve seen the footage and I’ve heard the conflicting stories about what informed that moment. I don’t want to be confused with going out into the world with some sort of declarative explanation of how it happened. What I want to say is, what a wonderful thing to have enough information at our disposal to take a deep dive as we want and then put together something that most of us can agree looks an awful lot like what surely must have happened and rally around the idea. Jack Lucas was real, for sure. We can prove it, but I wasn’t on that troop transport and I wasn’t there when his commanding officer dressed him down, but man, the cinema lover in me is there and I can imagine bringing that moment to life. For Independence Day, that’s a consummation devoutly to be wished.

Copyright 2024 TBN. Trinity Broadcasting Network. All Rights Reserved.

JOHN: I’m glad you brought up experts. There has never been a time in recent history where the experts are so doubted, and for such good reason. And you said it. There are experts on every side of every issue, and there’s not just two sides, there’s an infinite number of sides. And the end result is we trust none of the experts. And I feel like part of the power of you is you’re an everyman going through life, observing, telling us how you saw it and doing it in a way that is expert in every sense. Do you feel there is a hunger now for a different mode of engaging with information and how to make sense of the world, how to tell the story of the human experience? Are people hungry for that?

MIKE: Not hungry — starving, ravenous. I think the best way to explain it is that there are three and a half million podcasts today, where there were none twenty years ago. Have you ever gone through a museum, for the first time, and not really known where to go? Looking at things but not quite understanding? What you need in a moment like that is a docent. I was in Munich not long ago and I went to the Munich Museum, which is a wonderful and really detailed look at everything that led right up to the First World War, right up to the end of the Second. Five floors, panoramas, so much history and so much to take in. And I would have been lost had one of their experts not taken me by the arm and spent three hours walking me through it. That’s what we need. For the first time in history, we have now at our disposal 98% of all known information. In the history of the world, it’s right there on your device. It’s right there on mine. But we lack the compass. We’re like Magellan with no sense of direction out in the middle of the North Atlantic, with no sextant, no star. We’re all trying to dead reckon in the middle of a rough, tempestuous sea. And it’s scary. And so we look for stars. We look for harbingers. We look for guides. Sometimes it looks like Rogan. Sometimes it looks like Malcolm Gladwell for some. Other times it looks like Douglas Murray for others. (And if you haven’t seen that debate at the Oxford Union, I highly recommend it.) What it really means, I believe, is that the rules of persuasion are going to evolve. We’re going to look for our docents and we’re all going to have to balance this weird measure of earnestness and skepticism. Because, if I heard what I think was implicit in your question, we have to be skeptical. Skepticism is the armor to keep us from buying all of the soap from all of the soap salesmen, but the minute that skepticism is perceived by someone who disagrees, then we don’t become skeptical. We become “deniers,” just like that. And so, that’s where we are in the headlines today. My hope is that by looking at the headlines 160, 150, 80 years ago, we can start to see that we have been here before. Different tools, but same stakes, same species. We made it through stronger.

JOHN: Now your film is making its way into theaters – which is a major step. And we’re starting to see this with more independent media companies – getting their films on the big screen. In fact, the Daily Wire is partnering with Angel Studios to release the “Sound of Hope” on July 4. Where can people see your film – and where can they find it online?

MIKE: So we’re looking at about 1,000 theaters on June 27 that will premiere the film and it will run through the 4th of July, thankfully. Because that’s really why we did it. The trailer will give you a good sense. Go to: “Something To Stand For.” You can get tickets there. Look at some behind the scenes photos. How much time do we have? Because I’d be remiss if I didn’t share one quick thing with you.

JOHN: Please do.

MIKE: I spent a lot of time working in the medium where no second takes were allowed. That was “Dirty Jobs.” That kind of shooting was blisteringly honest and the opposite of deliberate. Making a movie is not. Making a movie is a script, and in this case, a script that revolved around nine pre–existing scripts that were all brought to life. In other words, everything was super intentional. And when I went to stitch it all together in D.C., we had a shot list and I had a director and there was a crew and we knew exactly what we needed to get before we got out of Dodge. And while I’m standing there in the World War II memorial, waiting for my cue — everything’s set up, we got the lights set up, and I’m gonna walk and talk and make some sounds, and it’s gonna be lovely — an honor flight shows up on the other side of the memorial. A dozen old men in wheelchairs, and their families are with them, and volunteers, and they’re being wheeled in. And I just couldn’t take my eyes off one of these guys. I said to the director, “Follow me over here, grab the camera.” His name was Andy Michael, he was 91. He was in Korea the same time my dad was and he had never been to this memorial. John, when you see tears streaming down a 91-year-old face … I asked him what it meant to be there. And the old guy looks around at all the stars that are on that wall and he and he looks back at me and he says what he says. You saw it. You saw the movie. So I’m telling you this because you know, even now, I’m out there with my plan. I’m pretty sure I know what I’m doing. I’ve been at this a long time and the whole purpose of the movie reveals itself in a completely unplanned moment. Now, what kind of schmuck would not put that in the film? I had to. And so, once again, it’s so humbling to find the thing you need in a place you weren’t even looking.

JOHN: It’s a beautiful, beautiful moment. I can’t actually speak about it. It gets to me too much. Mike, thank you so much for coming on.

MIKE: My pleasure.

JOHN: Great luck with this film.

* * *

Catch the full interview with Mike Rowe on the Saturday Extra edition of Morning Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)