It was quite possibly the most remarkable literary friendship of the 20th century.

As young men, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien both endured the utter devastation of trench warfare during World War I. Then, as unrivaled evil once again ravaged the European continent during the 1930s and ‘40s, these two Oxford professors produced epic works of fiction, masterpieces imbued with moral purpose and beauty.

Like many lovers of the classics, Joseph Loconte shares a lifelong fascination with Lewis and Tolkien. As a professor and scholar, Loconte marvels at how the writers produced their most beloved works in the dark crucible of World War II. So, why are their novels — and the films they inspired — still considered among the greatest of all time?

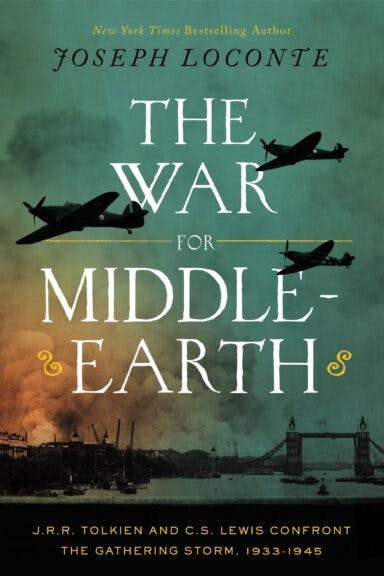

Glad you asked. This excerpt from Loconte’s new book, “The War for Middle-Earth,” may help light the way. — Joel Kneedler

* * *

Minds Lit by Fire

Halfway through the Great War, on November 30, 1916, a small group of European leaders managed to attend the funeral of Franz Joseph, ruler over the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In a ceremony scripted by the emperor before his death, the Grand Cortege carrying his coffin halted outside the Capuchin Monastery in Vienna, where all the Hapsburg emperors were laid to rest.

What transpired was a whisper from an earlier era, a nod to the transcendence of God and the frailty of men. The herald, on behalf of the emperor, knocked on the monastery door.

“Who is knocking?” shouted the abbot inside.

“I am Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria, king of Hungary.”

“I don’t know you.”

Again the herald shouted: “I am Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria, king of Hungary, Bohemia, Galicia, Dalmatia, Grand Duke of Transylvania, Duke of—”

“We still don’t know who you are,” interrupted the abbot.

At this moment the herald fell on his knees and in front of all assembled declared, “I am Franz Joseph, a poor sinner, humbly begging God’s mercy.”

“Enter then,” the abbot said. And the gates opened.

The funeral of the Austro-Hungarian emperor symbolized an outlook already in an advanced stage of decay. Settled beliefs about the religious dimension to human life were becoming unsettled. Assumptions about the moral life, about the existence of good and evil, seemed to have vanished into the killing fields of the 1914–18 war. By the end of the war, the emotional and spiritual lives of millions of ordinary Europeans were caught up in a no-man’s-land of doubt and disillusionment.

Two of the most influential writers of the twentieth century, J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, were soldiers in the Great War. They fought in the trenches in France, what one contemporary called “the long grave already dug.” They emerged from the mechanized slaughter of that conflict physically intact—just barely.

No man could pass through the fires of the Somme and Arras and remain unchanged. For Tolkien, his war experience created an enduring sense of sadness. Yet he found that his imaginative cast of mind, his early taste for fantasy, was “quickened to full life by war.” For Lewis, the conflict deepened his youthful atheism: the growing conviction that if God existed, he was a sadist. Paradoxically, the war years launched Lewis on a spiritual quest, a desire for “Joy,” which ultimately led him on a remarkable journey of faith.

The lives of these two men intersected after the war as they were launching their academic careers at Oxford University. They soon formed a bond of friendship that, given the reach and influence of their novels, must rank as one of the most consequential friendships of modern times.

There was nothing inevitable about it. Tolkien was a devout Catholic; Lewis an Ulster Protestant and lapsed Anglican. At their first English faculty meeting, they circled each other like tigers in the wild. Yet they soon discovered that they loved many of the same things: ancient myths, epic poetry, medieval stories of honor, chivalry, sacrifice, and war.

The theme of war would become a defining feature of their professional and literary lives. Their personal lives would be upended by two global conflicts. Barely twenty years after surviving what was the most devastating conflict in history, Tolkien and Lewis would watch in anguish as new forces of aggression gathered and dominated the geopolitical landscape of Europe.

In 1938, a year before the outbreak of the Second World War, author H. G. Wells terrified millions with a radio broadcast based on his novel The War of the Worlds, in which an imaginary Martian invasion devastates the earth. Art would imitate life. As British historian Niall Ferguson observes, “men proved that it was quite possible to wreak comparable havoc without the need for alien intervention. All they had to do was to identify this or that group of their fellow men as the aliens, and then kill them.” This was the terrible pattern in the aftermath of the First World War. Communism, fascism, Nazism: all produced political systems that drew their strength from their hatreds.

The totalitarian states of Europe and Asia, despite their differences, shared another unifying characteristic: a contempt for the democratic and religious ideals of the West. Their ambitions made another global conflict almost inevitable.

“If the first great war was the seminal catastrophe,” argues historian Sir Ian Kershaw, “the second was the culmination of this catastrophe—the complete collapse of European civilization.” Living and working in Oxford, England, Tolkien and Lewis found themselves at the storm front of this tragedy. Like no other conflict in Britain’s long history, the Second World War created an existential crisis. For many months the political survival of their island nation was an open question.

It was in the crucible of this experience that Tolkien and Lewis sought each other out. The horror of the First World War instigated a cultural backlash, setting loose forces that tore at the moral and spiritual foundations of Western civilization. Both men were determined to fight back. They formed the nucleus of a group of like-minded writers, all resolved to establish a beachhead of resistance in the war of ideas that was raging around them.

The onset of the Second World War created a profound sense of urgency. Tolkien and Lewis came to believe that the soul of their neighbor, as well as the soul of their civilization, hung in the balance. In ways not fully appreciated, the 1939–45 war utterly transformed their lives and literary imaginations. Their most beloved works — including The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and The Chronicles of Narnia — were conceived in the shadow of this conflict.

“Talent alone cannot make a writer,” observed Ralph Waldo Emerson. “There must be a man behind the book.” Behind the extraordinary works of Tolkien and Lewis stood a cloud of witnesses: individuals whose contributions to the literary canon of Western civilization provided the inspiration for their epic novels. Both authors instinctively looked to this inheritance and were nourished by it in wartime.

As a result, they acquired something that our modern era has mostly abandoned: perspective. By being rooted in the great books of the Western tradition, they knew where to look for wisdom, virtue, courage, and faith. Intimate knowledge of the past braced them for the crisis years of 1933–45. In this, they reinforced each other’s best instincts. “My entire philosophy of history,” Lewis once told Tolkien, “hangs upon a single sentence of your own.”

Could an entire philosophy of history be summed up in a single sentence? What sentence? It is from a passage in The Lord of the Rings, when Gandalf the Wizard explains to Frodo Baggins something of the ancient struggle for Middle-earth. “There was sorrow then, too, and gathering dark, but great valor, and great deeds that were not wholly vain.” Here is an approach to history — to the terrible history of the twentieth century — that invites reflection.

The lives of Tolkien and Lewis, after all, were embedded in this story when another disastrous war unleashed upon the earth a storm of human misery unsurpassed in the catalogue of world catastrophes. “Middle-earth, I suspect, looks so engagingly familiar to us, and speaks to us so eloquently,” writes biographer John Garth, “because it was born with the modern world and marked by the same terrible birth pangs.” We cannot fully appreciate the achievement of these two remarkable authors until we try to see the world as they experienced it. They possessed a deep awareness of life’s sorrows.

Yet this is only part of their story. Their experience of suffering was held in check by something stronger: gratitude. The Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero called this quality “not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all the others.” Like no other authors of their age, they used their imagination to reclaim—for their generation and ours—those deeds of valor and sacrifice and love that have always kept a lamp burning even in the deepest darkness.

* * *

Adapted from “THE WAR FOR MIDDLE-EARTH: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Confront the Gathering Storm, 1933-1945,” by Joseph Loconte. Copyright 2025 by Joseph Loconte. Published by Thomas Nelson. Available wherever books are sold on November 18, 2025.

* * *

Joseph Loconte, PhD, is an author, historian, and filmmaker. He serves as Director of The Rivendell Center in New York City. He is a Presidential Scholar at New College of Florida and a Senior Fellow at the Sagamore Institute. Mr. Loconte’s commentary appears in outlets such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, National Affairs, The New Criterion, National Geographic, Law and Liberty, The National Interest, and National Review. For ten years Mr. Loconte served as a commentator for National Public Radio’s All Things Considered. A native of Brooklyn, New York, he divides his time between Washington, DC, and New York City.

* * *

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)