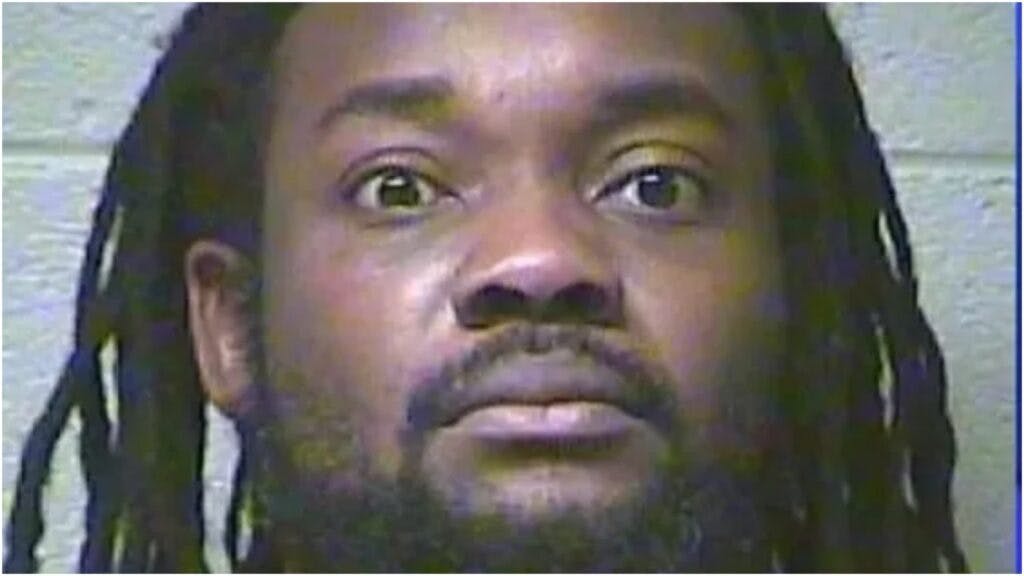

When we outlined the crimes of 42-year-old Ronald Exantus yesterday, it was very difficult to imagine how the story could possibly become any more disturbing, infuriating, and insulting to our intelligence than it already was.

As we reported, Exantus brutally murdered a six-year-old child in Kentucky named Logan Tipton in December of 2015, before violently attacking Logan’s siblings and his father. He stabbed Logan’s sister and threw his father across the room, seriously injuring him. On the night of the crime, Ronald Exantus admitted to officers that he deserved to die for what he had done.

Kentucky Department of Corrections.

But he wasn’t put to death. Instead, the jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity for killing Logan Tipton, and guilty of “assault” in the attacks on everyone else in the family. As a result, he’s now a free man. For a home invasion in which he slaughtered a child, Ronald Exantus ultimately served less than a decade in prison — in a state that’s overwhelmingly conservative, no less. In other words, unless the slain child’s father murders Ronald Exantus — as he’s vowed to do — then this particular child killer won’t suffer any meaningful form of justice for his crimes. In the state of Kentucky, child murder is now treated like tax evasion. The punishments are equivalent.

That’s how things stood, as of yesterday. Somehow, though, this story has just become even more incomprehensible and enraging. The more you look into what happened here — and how it happened — the more you realize that drastic action needs to be taken. And after looking into it over the last 24 hours, I have a pretty good idea of how to go about that.

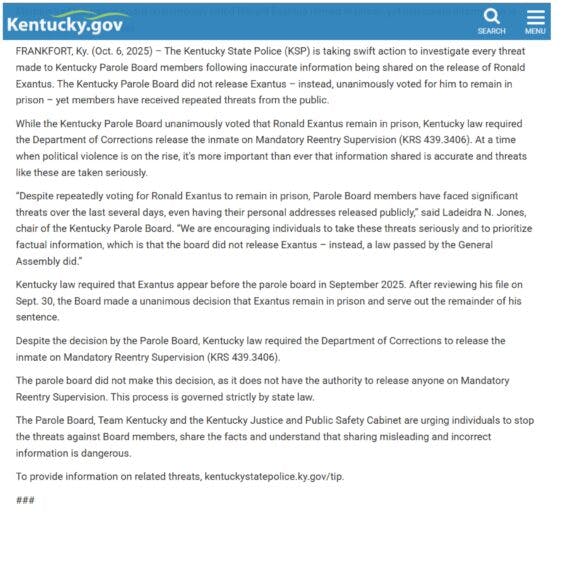

We’ll start with this new statement from the Kentucky Parole Board. They claim that, really, they didn’t have anything to do with the release of Ronald Exantus.

Kentucky.gov

It reads:

Despite repeatedly voting for Ronald Exantus to remain in prison, Parole Board members have faced significant threats over the last several days, even having their personal addresses released publicly. We are encouraging individuals to take these threats seriously and to prioritize factual information, which is that the board did not release Exantus – instead, a law passed by the General Assembly did.

First of all, you’ll notice that they make themselves the victims in this scenario, right off the bat. Forget about the grieving parents, who have to watch their son’s killer go free. Forget about Logan’s siblings, who are traumatized for life — and who now have to worry that Ronald Exantus will kill them, too. Forget about all the millions of Americans who have lost faith in the judicial system as a result of this farce. The real victim, according to the Kentucky Parole Board, is the Kentucky Parole Board.

Of course, no one should threaten the Kentucky Parole Board. But you have to wonder why their first instinct is to talk about themselves, in a case like this. You also have to wonder if they actually voted to keep Ronald Exantus in prison, since the parole board’s meetings aren’t public. We’ll just have to take their word for it, I suppose. And more importantly, you have to wonder what “law passed by the General Assembly” is responsible for the release of Ronald Exantus — and whether or not the parole board could’ve done anything about it.

This is where the story becomes truly insane. When my producers reached out to the Kentucky Parole Board, they informed us that Ronald Exantus — who, again, broke into a home in the middle of the night, murdered a child, and tried to kill an entire family — is actually considered a “non-violent offender” in Kentucky. Yes, you heard that correctly. A man who stabbed a child to death so viciously that the blade bent, and who then tried to kill the child’s siblings and his father, is a non-violent offender.

This is directly from the Kentucky Parole Board’s spokeswoman, in her conversation with my producers:

His conviction … classifies him as a nonviolent offender. … Violent offenders have to serve at least 85% of their sentence. With his conviction being non-violent, the time he earned in the areas — jail credit, good time credit, education credit — reduced his sentence.

To put it another way: If you’re a non-violent offender in Kentucky, you only have to serve 20% of your sentence. If you’re a violent offender, you have to serve 85%. And a conviction for second-degree assault, which is what Ronald Exantus received for attacking the father and his children, is considered non-violent.

This didn’t seem like it could possibly be real. But indeed, it’s the law of the land. In Kentucky, you can stomp on someone’s head, breaking their bones and forcing them to black out, and still be considered a “non-violent” offender.

Get 40% off new DailyWire+ annual memberships with code FALL40 at checkout!

That happened in a recent case. Only if you’re convicted of first-degree assault (as opposed to second-degree assault) are you considered “violent.” And the only difference between first-degree assault and second-degree assault is that, in first-degree assault, you inflict “grave” life-threatening injuries that bring someone to the absolute brink of death. And second-degree assault is everything else. You’re “non-violent” if you violently attack someone, as long as your violent attack doesn’t leave their head dangling from their neck. (Oh, and by the way, if you’re a “non-violent” felon, then you can keep your voting rights. You also have a much easier time getting your record expunged. So there are perks to being a violent psychopath who happens to be “non-violent” at the same time.)

This law, which has been approved several times by the Kentucky legislature over the past decade, must change immediately. The idea that a home invader who violently attacks every single one of his victims, including children, is really “non-violent” — is such an obviously outrageous suggestion that no reasonable person can possibly defend it. The only rational assumption that can be made, in this case, is that lawmakers in Kentucky didn’t realize what they voted for. They must have just signed off on this legislation without thinking through the implications or reading the legislation at all. That’s the best-case scenario. The worst-case scenario, of course, is that they want child killers to go free as quickly as possible. You’d hate to think that would be a possibility. But it’s hard to come to any other conclusion if they don’t change this law.

Keep in mind, the Ronald Exantus case is several years old. He was convicted of this “non-violent” offense in 2018. He was found “not guilty by reason of insanity” in 2018. Kentucky lawmakers have had since 2018 to respond to this outrage by changing the law, and they haven’t.

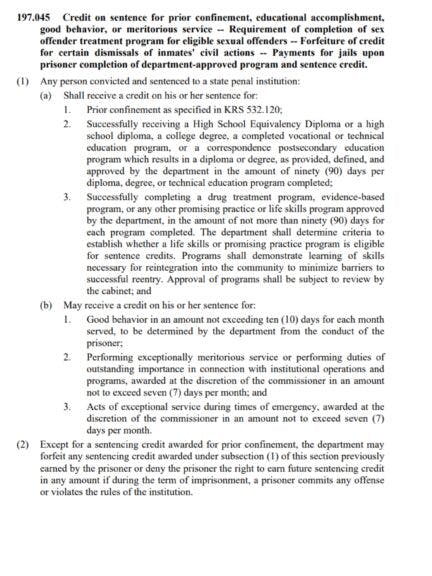

At the same time, it’s also not the case that the Kentucky Parole Board is absolved of all responsibility here. It’s true that, for “non-violent offenders,” very large sentencing reductions are possible.

As you can see, inmates can receive 10 days of credits for each month served if they behave well. They can receive 7 days of credits per month if they perform “meritorious service” while in prison. And they can receive another 7 days of credits per month if they do something “exceptional” during an emergency. Additionally, inmates can receive roughly half a year in education credits and drug treatment programs. Add this all together, throw in time served, and it’s not unusual, from a purely mathematical perspective, for someone with a 20-year sentence to get out of prison in less than a decade, which is what happened here.

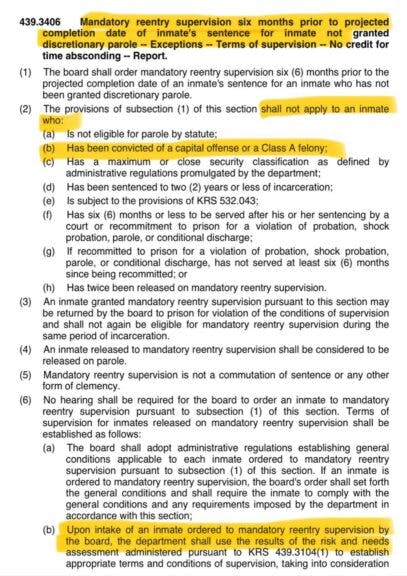

But the parole board still doesn’t have to unleash child killers on the public with no strings attached. It’s true that the law indicates that the state “shall” release inmates once their credits allow for it. But the parole board is entitled to add conditions, on a case-by-case basis, that the convict has to follow after he’s been released.

And if any of those conditions are violated, he has to go back to jail.

Upon intake of an inmate ordered to mandatory reentry supervision by the board, the department shall … establish appropriate terms and conditions of supervision.

So what conditions, if any, were placed on Ronald Exantus? We don’t know the answer to that question. The parole board hasn’t said anything about it. And they haven’t responded to our questions on the topic, either. And that suggests, of course, that no serious conditions were imposed — or at least, nothing out-of-the-ordinary was imposed. And if that’s the case, it’s yet another travesty of justice in this case. Any reasonable parole board would do everything in its power to put this killer back in prison. If the law requires his release, then you still have the capability to do everything in your power to protect the community with the most demanding, restrictive post-release conditions imaginable. And in the meantime, you should be calling for a change in the law. It shouldn’t take podcast hosts and Twitter users to do that for you. If the Kentucky parole board was really forced by the law to release Ronald Exantus, why haven’t they all been in front of cameras every day screaming to the heavens about this outrage that they were forced by law to participate in? Why aren’t they working tirelessly to make the changes that need to be made? Why didn’t they all resign rather than rubber-stamp this release? There are many things that they could have done and should have done if they wanted to be the good guys in this situation. But they didn’t do any of those things.

And the most important change that needs to be made — and this is true across the country, and not just in Kentucky — is that so-called “insanity defenses” must be drastically reined in, if not abolished entirely. We didn’t always have “insanity defenses” in this country. In the early 19th century, when juries acquitted someone because he was “insane,” it was really a form of jury nullification. They were excusing a crime of passion — like when Daniel Sickles, a congressman, shot the U.S. Attorney for D.C. because he was having an affair with his wife.

Later on, when states adopted a formal definition of “insanity,” they didn’t all agree on the same precise rules. They still don’t. But today, by far, the most widely used definition of insanity in most states — including Kentucky — involves a two-part test. If a defendant fails either prong of the test, then he’s insane. Prong number one: Does the defendant understand the nature and quality of the act he’s committed? In other words, instead of firing a gun, did he genuinely think he was, say, blowing a feather or something like that? If the defendant fails this test, then he’s insane. Of course, one of the big problems is that you can’t possibly know whether he understood what he was doing. All you can do is ask him. And the criminal has every incentive to lie.

But even if a defendant *does* understand what he’s done, he still has a potential insanity defense. That brings us to prong number two: Did the defendant know what he was doing was wrong? Or was he so far gone that he couldn’t distinguish right from wrong? If so, he’s insane. And under the law in Kentucky, he can’t be held responsible for murdering a child.

This second prong, at least, needs to be eliminated from the law. It’s simply far too easy to abuse. And everyone should be able to see why. Someone who doesn’t understand right from wrong is not insane. He’s not suffering from a medical condition. There is a word we used to use for people like that. It’s called evil. Nobody commits an evil act thinking or admitting to themselves that it’s evil. Every atrocity, every genocide, every mass shooting, has been committed by someone who believed or told themselves that it was for some reason necessary or justified. So if that is the definition of insane, then every evil act is an act of insanity, and nobody should ever be punished for anything.

Once you start making excuses for people who can’t separate right from wrong, and pretend they’re “victims” in need of some therapy and some pills, you provide a ready-made legal defense for some of the most evil and dangerous psychopaths on the planet.

In the case of Ronald Exantus, the defense team wasn’t even able to demonstrate that he suffered from any specific mental disorder. They didn’t have to. All they had to do was argue that he suffered from some kind of vague mental fog. And that was enough for an acquittal on first-degree murder. But defense lawyers have been adopting this strategy for a very long time. It’s nothing new.

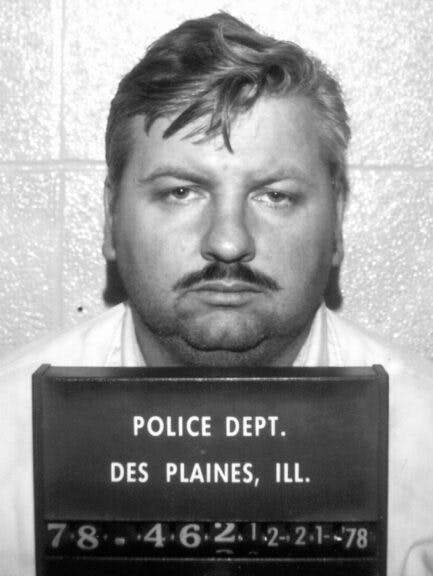

Des Plaines Police Department, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When John Wayne Gacy was on trial for murdering dozens of young men and boys, and burying their bodies in a crawl space and tossing them in the river, his lawyers argued that he was insane. After all, what kind of person would murder so many people? Obviously, he didn’t know right from wrong. He must not have understood precisely what he was doing, in the way that all of us do.

In Gacy’s case, the jury didn’t buy it. But in other, similar cases, they did. Take the case of Albert Fish, for example.

SOURCE: Wikipedia. New York Daily News.

In the 1920s, he murdered and molested several children. He was also a cannibal. The crimes are too horrific to describe. But the point is, at trial, a psychiatrist was asked whether Fish knew the difference between right and wrong. The psychiatrist responded that he did know the difference, but that his knowledge was “perverted based on his opinions of sin, atonement, and religion, and thus was an insane knowledge.”

It’s obviously hard to make sense of what that means. It’s doublespeak. And that’s a big part of the problem with the insanity defense, in general. In many cases, psychopaths will think they’re doing something that’s “right.” They might not understand general norms about “right and wrong,” either. So what do we do with them?

In the case of Albert Fish, the jury had a solution. They decided that Fish was insane by any conventional definition. But they convicted him anyway. They simply discarded all of the ridiculous contortions about “insanity” that the lawyers were talking about. So Albert Fish was sent to the electric chair and executed.

That’s how every criminal defendant who commits a depraved act of psychopathic violence — like Ronald Exantus — should be treated by our legal system from now on. Forget the academic discussions of “insanity” or who understands right and wrong and who doesn’t. If a criminal commits a heinous and unspeakable act of violence, he should be executed.

This is an approach we need to adopt as quickly as possible, because every other day, a new violent felon is being released from prison — or not tried at all — on the basis of a fraudulent insanity defense. Just a few weeks ago, we discussed the case of an 18-year-old named Cora Vides, who ambushed her friend for no apparent reason in her home. She stabbed her friend so many times in the neck that she lost her ability to speak. At trial, she was found not guilty by reason of insanity, which in California means she could be out of prison in a few months.

Then there’s this case from Aurora, Colorado:

A man accused of attempting to kidnap an elementary school student during recess last year is expected to have his charges dropped. According to multiple outlets, the 18th Judicial District Attorney’s Office in Colorado intends to dismiss charges against Solomon Galligan. The 33-year-old was arrested and charged with attempted kidnapping in April 2024. … Eric Ross, a spokesperson for the 18th Judicial District Attorney’s Office, shared that a doctor has found Galligan incompetent to stand trial last month. … Authorities said Galligan has a criminal history, which includes a 2012 conviction for failing to register as a sex offender.

In cases like this, the defendant goes to a psychiatric facility. And then at some point in the future, he’s released, with no criminal record whatsoever. That’s what happened with Ronald Exantus. He was found not guilty by reason of insanity for murdering Logan Tipton. In theory, that means he’d have to spend an indefinite period of time in a psychiatric hospital. But in practice, after he stops taking drugs, he’s suddenly normal again — so he’s allowed to go free.

Here’s a similar story from the New York Post:

A woman who authorities say fatally stabbed a 3-year-old boy as he sat in a grocery cart outside an Ohio supermarket and wounded his mother has been found incompetent to stand trial. … Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Judge John Russo issued the ruling Friday. He said Bionca Ellis, 33, of Cleveland, will remain hospitalized indefinitely and could eventually stand trial if she improves.

We shouldn’t have to wait for a trial in any of these cases. We shouldn’t give doctors any leeway to unleash these killers on the public, nor should we allow parole boards to tally up “good time credits” so that criminals are released 10 years early. There should be an immediate trial within a week. And if you’re found guilty of killing a child, or trying to kill a child, then you should die. That’s a very workable system. We’ve had it in the past. We should adopt it again. There is no downside at all, except the considerable downside experienced by the child killers. But if your first priority in dealing with child killers is to protect them from uncomfortable experiences, then you are nearly as evil as they are. And I mean that sincerely.

In the meantime, in Kentucky, everyone from the state legislature to the parole board needs to take action, immediately, so that Ronald Exantus — and everyone like him — is returned to prison as quickly as possible. Stop pretending that violent attacks, where someone clearly tries to kill another person, are somehow “non-violent.” Stop conflating evil with insanity. And above all, stop conflating “insanity” with something that anyone in society should have to deal with. Once you are insane to the point that you kill or attempt to kill another human being, you deserve the Albert Fish treatment. Nothing more, and nothing less. Your lawyers can prattle on about how you’re nuts, and how you have no idea what’s going on, and so on. And in response, we can — and we must — do exactly what the jury did in Albert Fish’s case. We shouldn’t listen to a word of it. And then we should put you to death. And then we will have some semblance of justice in our country again.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)