As President Donald Trump focuses on tax reform, his administration is reportedly considering adding a value-added tax (VAT) and a carbon tax to offset revenue losses from tax cuts. This suggests that the Trump administration is abandoning their previous consideration of a border-adjustment tax due to political implications. The administration has not officially decided if they want to add a VAT and carbon tax to the tax system or not.

Here are seven things you need to know about the VAT.

1. A VAT is a national sales tax that taxes every level of production. Investopedia explains,”when a television is built by a company in Europe, the manufacturer is charged VAT on all of the supplies it purchases to produce the television. Once the television reaches the shelf, the consumer who purchases it must pay the applicable VAT.”

Additionally, VATs don’t allow employers to deduct wages from their taxes, meaning “that employers have to pay a VAT on any compensation they give to workers,” according to the Cato Institute’s Daniel J. Mitchell.

2. A VAT is invisible to the consumer. State and local sales taxes are seen on receipts; VATs are not. Consequently, consumers only see the higher prices that come along with the added cost of a VAT but don’t see that the VAT is responsible for them. The VAT then provides politicians with a golden opportunity to raise taxes without fearing political backlash, which is why they dangle it as a low tax at first and then raise it over time. For instance, a 2015 Wall Street Journal editorial pointed out:

E&Y says standard VAT rates now average a knee-buckling 21.6% in the European Union, up from 19.4% in 2008. Average standard rates in the industrial countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have climbed to 19.2% from 17.8% in 2009.

Japan is another example of the VAT upward ratchet. The Liberal Democratic Party tried to introduce the tax for years and finally succeeded with a 3% rate in 1989. Eight years later the shoguns raised it to 5%. Last year it climbed to 8%, whacking consumption and sending the economy back to negative growth. The rate was scheduled to hit 10% later this year, though the government has delayed it until 2017. Rest assured the 10% rate is still coming. And it will keep climbing.

3. A VAT will never be visible to the consumer. Economist David Henderson wrote in a Wall Street Journal column that governments that allow the VAT to be visible face severe political backlash. He pointed to the landslide defeat of Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative party in the 1990s as an example, since Mulroney “imposed a fully transparent 7% sales (consumption) tax” in 1991.

“In the next election, his party lost nearly all of its 151 seats—the biggest rout in Canadian parliamentary history,” wrote Henderson. “The hugely unpopular sales tax was a major contributor.”

Therefore, it’s highly unlikely that a VAT would ever be visible to the consumer if implemented in the United States.

4. It is a regressive tax. The reason it is regressive is because, according to Carnegie Mellon Professor Alan Meltzer, “average spending declines as income rises,” therefore the poor and middle class disproportionately take the brunt of a VAT. Typically countries that implement VAT attempt to ameliorate the regressive nature of the VAT by providing tax rebates to the poor, opening the door to fraud and increasing the debt.

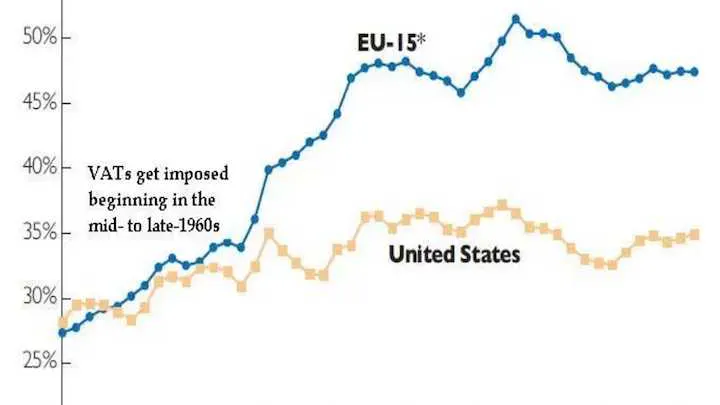

5. European nations have adopted VATs, resulting in the expansion of their welfare states. Mitchell highlighted the following graphic in a Townhall column:

Clearly, the VAT provided European countries with another revenue stream for them to binge on with their respective welfare states, meaning that the VAT resulted in more spending, more debt and less money in the hands of taxpayers. There’s no reason to think that the same wouldn’t happen if a VAT is implemented in the U.S.

6. VATs would be detrimental to the economy. According to Meltzer:

The collection costs are borne by the sellers, and the full tax is paid by the consumer. The tax is costly to collect and to monitor. To avoid the tax, people pay for services in cash. The service provider does not report the sale and also avoids paying income or other taxes. The so-called underground economy grows. Because the VAT raises the price faced by the consumer, spending declines.

This is why state and local governments oppose the VAT, because the decline in spending affects their revenue as well. Naturally, the decline in spending also weakens the economy.

7. VATs are also subject to political cronyism. The Journal editorial pointed out that politicians can’t help but provide more favorable VAT levels toward industries that benefit them politically, such as Luxembourg providing a three percent VAT level for refurbishing properties for rent despite a 15 percent VAT everywhere else and Spain imposing a 21 percent VAT on specific cleanliness products.

The U.S. is unique in being an industrial nation without a VAT; if Trump and the Republicans decide to impose one on the American people it would only put the U.S. one step closer toward being like Europe and away from America’s exceptional heritage of being founded through principles of individual liberty and limited government.

.png)

.png)