A jury has awarded a former Pacific University student nearly $4 million after he was falsely accused of sexual assault and removed from his doctorate program without due process.

Peter Steele enrolled in Pacific University, located in Washington County, Oregon, in the fall of 2016 to obtain a Doctor of Psychology. Between March and June of 2020, Steele began a sexual relationship with a fellow student in the program, Abigail Masters.

The two texted throughout this relationship, with texts relating to the specific sexual and intimate acts between the two showing their relationship had been consensual. These text messages increased significantly after their first sexual encounter, with texts becoming “more extensive, detailed and specific,” Steele wrote in his lawsuit against Masters and Pacific.

In particular, the texts, according to Steele’s lawsuit, reveal that Masters asked Steele to engage in behaviors she would later claim as nonconsensual. She would also become upset if Steele didn’t respond to her enthusiastically when she asked for additional sexual encounters.

Masters even, according to the lawsuit, threatened to drive past Steele’s apartment and expose their affair to Steele’s other romantic partner if he didn’t sufficiently respond to Masters’ requests. She would later admit to actually driving past his apartment around midnight on the day she made the threat.

After their final sexual encounter around June 16, 2020, Masters repeatedly tried to get Steele to engage in additional sexual activity, even texting him, “When are you going to f*** me again?”

When Steele didn’t respond to Masters’ requests, she went to Pacific administrators and accused him of physical and sexual assault beginning around June 22, 2020. Thus started a chain of events that led to Steele being removed from his graduate program.

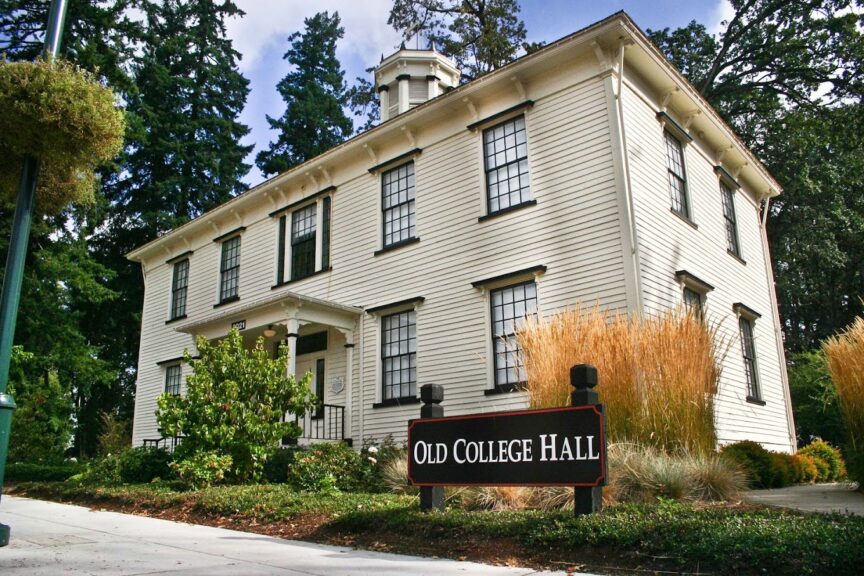

Credit: Brass Tacks.

Steele was not even aware that anything was wrong until July 2, 2020, when his doctorate program’s director, Dr. Jennifer Clark, emailed him saying that she and Tamara Tasker, a professor and director of academics for Pacific’s School of Graduate Psychology, needed to speak with him.

Clark didn’t give any specifics as to what the meeting was about, only saying that they needed to “discuss something that has come up.”

Steele met with the women that morning, and was told that a complaint had been brought against him, so they were temporarily removing him for clinical training. Steele said in his lawsuit that he was given no additional information about the complaint, or even that it was sexual in nature. Further, Steele wasn’t told of what he was accused, what process would occur to resolve the complaint, what rights he had, or opportunities he would have to defend himself.

According to Pacific’s own policies, the school was required to provide the accused notice of what he had been accused of, the actual policy he was being accused of violating, information about the procedure that would be followed to determine responsibility, a fair and neutral investigation with a chance for Steele to defend himself, and a hearing before an impartial panel if deemed necessary by the investigation. In addition, the burden of proof was supposed to be placed on Pacific and Masters to prove Steele’s responsibility, not for him to have to disprove the allegations against him. The school was also required to provide him a meaningful appeal process.

Throughout the year-long ordeal, Steele was never granted any of these rights.

Through the lawsuit process, Steele learned that days after his meeting with Clark and Tasker, an employee acting as Pacific’s general counsel, Jennifer Yruegas, emailed Masters to provide her a document listing all the resources she had, as well as connecting her to the school’s director of student conduct and interim dean of students Lindsey Blem. Yruegas also asked for Masters to keep her informed of any law enforcement involvement, as Masters had also made her allegations to police. After a police investigation, which allowed Steele to provide the text message evidence, the Washington County District Attorney’s Office declined to bring any charges against Steele.

Masters was never charged with making a false report.

After reaching out to Masters, Yruegas emailed Professor Tasker, and asked in the subject line: “What will be the timing for pulling the student from placement – what do you need from me?” In the body of the email, Yruegas said that the Title IX process has been “kicked off.”

Title IX is a statute that prohibits schools from discriminating against students based on their sex, and has been used in the past decade to justify pseudo-adjudications of sexual assault claims.

Lindsey Blem, Pacific’s interim dean of students, also emailed Masters to let her know about the process that would be used during the investigation and what rights she had under school policy. Blem also encouraged Masters to use those rights.

After days of hearing nothing, Steele emailed Clark asking if there was any new information about the complaint.

Four days later, Clark responded saying that she and professor Tasker were still looking into the matter and would let him know when they had more information. Again, Steele was not given the specific allegations against him or advised of his rights.

On the same day, however, general counsel Yruegas emailed professor Tasker with a subject line that read; “Help For Abigail [Masters].”

The day after Clark finally responded to Steele, Blem emailed general counsel Yruegas saying the conduct process was “on pause” but that they would “likely need to get things moving soon.” She then asked if anyone had told him why this process was occurring.

On July 15, Steele responded to the email Clark asking if she could find out what was going on “ASAP,” adding that it had been two weeks since he was first informed about the complaint. He asked for specific information, including the nature of the complaint, the process, and what he could do to address the issue.

A week later, on July 24, Masters herself asked Yruegas and Blem to put the investigation on hold. Blem agreed.

By July 28, more than a month since the complaint was filed, Clark forwarded Steele’s email from July 15 to general counsel Yruegas, asking how she should respond and who she could direct Steele to so he would stop asking her for guidance. Clark also raised concerns about keeping Steele from his Fall clinical placement since things could resolve in his favor.

Credit: Pacific University

For days, Pacific administrators emailed each other discussing what they should disclose to Steele about the investigation and allegations – and whether they should disclose anything at all. On August 7, 2020, Clark replied to Steele’s email from a month earlier, saying she couldn’t answer all his questions, but said that “Information was provided that was concerning and required review,” but that the review was inconclusive. She added that he would be able to move forward with his Fall clinical training unless new information arises that could reverse that decision.

Throughout all of this, Pacific administrators kept in contact with Masters and supported her, continually advising her of her rights without doing the same for Steele.

With Steele believing he would return to his clinical training in the coming semester, Masters filed a petition for a restraining order in Washington County Circuit Court. Masters accused Steele of physically and sexually assaulting her. Because the petition only requires the accusations and provides no avenue for the accused to defend themselves, Masters was granted the restraining order, which she promptly shared with general counsel Yruegas and Professor Tasker.

Masters also obtained two attorneys to help her proceed with her campaign against Steele. The attorneys asked Yruegas about the status of the Title IX investigation.

On September 3, Yruegas apologized to the attorneys by saying they were dealing with COVID-19 testing and reminded them that Masters had asked that the investigation be put on hold. In this email, Yruegas said that because of the restraining order, they would be suspending Steele, and using that along with Masters’ police report and complaint, they would move forward with the Title IX investigation that could expel Steele.

Later that day, program director Clark emailed Steele to say that they had been notified of the restraining order and would suspend him from the doctorate program. She also informed him that there was no appeal process with the School of Graduate Psychology, but he could appeal the decision at the college level and then at the university level. He was advised to reach out to Blem, Pacific’s interim dean of students, who had been advising Masters.

No Pacific policy said that a restraining order under these circumstances (with no right to defend himself) was grounds for suspension. Further, almost all of Steele’s graduate activities had become remote due to the pandemic, so he posed no threat to anyone.

Program director Clark emailed Steele again with more information about the appeals process, saying that he could only appeal if he provided “clear indication” that there was an error in procedure, new evidence sufficient to alter a decision came to light, or the imposed sanctions were inappropriate for the violation.

Steele believes the information about the appeal process was added in to help Pacific better conform to one of its policies, even though no policies had been followed thus far.

A Pacific employee emailed Clark and Professor Tasker to say that she was removing Steele from classes even though they normally wait until all appeals have expired.

Devastating to Pacific’s case in Steele’s lawsuit, the dean of Pacific’s School of Graduate Psychology sent an email as part of a series of internal communications surrounding the allegations against Steele, copying and pasting sections of the school’s handbook containing policies for dealing with these allegations.

Masters’ attorneys asked for an update, and general counsel Yruegas said that Steele had been suspended and the school would continue with a Title IX investigation as soon as Masters sent an email or signed statement regarding her allegations.

By now, Steele had retained an attorney, who repeatedly attempted to get answers from Pacific representatives but largely failed. The attorney, Kevin Sali, on numerous occasions called and emailed Yruegas to get answers to basic questions, such as the basis for its suspension and the allegations against his client. Yruegas finally responded brusquely, saying that student handbooks were available for each student and appeals procedures are outlined therein. This is a far cry different than the support and encouragement the school provided Masters.

On September 18, 2020, Steele appealed his suspension, saying he had no idea what procedure had been followed so he couldn’t point out a specific violation, but could not find any procedures that matched what had occurred in his case. He also noted that he had never been told what the allegations against him were, but denied everything that Masters had accused him of when she obtained the restraining order. He pointed out that at no time was he given an opportunity to deny or provide evidence against these allegations by Pacific administrators.

Steele also said there was new evidence that could alter the decision – his denial, since he was never given a chance to make one. Further, Steele said that his suspension was not appropriate because Pacific had not established that he even engaged in any improper conduct.

His appeal was denied.

He was advised that he could appeal at the university level and provided the same information as before and again directed him to interim dean of students Lindsey Blem, who had previously provided him no guidance and had been supporting Masters.

Steele appealed again, and again was denied.

On October 23, general counsel Yruegas met with Masters’ attorneys and provided additional guidance and support – something they never provided Steele. Steele wrote in his lawsuit that between October 23 and 26, it is believed that Yruegas discussed with Masters’ attorneys alternative ways the school could pursue her allegations against Steele.

On October 26, Masters’ attorney emailed Yruegas with information about a 2006 misdemeanor conviction against Steel from McLennan County, Texas. Steele later learned that this was not the first time Masters had brought up the misdemeanor, and had done so early on in the accusation process. Masters’ questions caused Professor Tasker to look into Steele’s application to the school’s graduate program and his background check.

Steele said in his lawsuit that he had made “multiple and extensive disclosures” to Pacific administrators about this misdemeanor conviction and had written about it on his application form when asked if he had ever been convicted of a crime. He even told program director Clark specifically about the conviction. He was still allowed into the school.

Yet now it was being brought up again. Steele would soon find out why.

Back in August, when Masters petitioned the court for a restraining order against Steele, he requested a hearing to contest her allegations. The hearing took place on three separate occasions, and ended with a judge determining Masters’ allegations had no merit.

Specifically, the judge said it was “very difficult for [him] to find that those were not consensual acts” after reviewing the text messages between Masters and Steele and that “the messages that occurred right around each one of these incidents really kind of pulls a rug out from the statements that [Masters] made in her petition and on testimony about whether or not these were consensual acts.”

With the restraining order lifted, Steele informed the school.

On January 5, Masters’ attorneys asked if Steele had been reinstated and asked if he would be able to appeal his suspension. General counsel Yruegas responded by saying there “is no appeal possible.”

The attorneys further spoke about the restraining order hearing, emphasizing Masters’ testimony, prompting Yruegas to say she believed that testimony would “be enough to stave off any further requests we receive,” purportedly from Steele. Yruegas also asked the attorneys to “pass on my best to Ms. Masters.”

Throughout this time, Pacific administrators were not communicating with Steel or his attorney, despite repeated inquiries. The next time they received communication was on June 8, 2021 – nearly a year after Masters had made her initial allegations. Program director Clark informed Steele that he was being dismissed from the program because he allegedly “misrepresented your criminal background in your admissions application.” She also provided all the same appeal information as before.

Steele knew this was just a way for Pacific to get him out of the school without allowing him to disprove Masters’ allegations. He appealed, again noting that no procedure had been followed and he never had a chance to defend himself.

His appeals were denied again.

So he sued, and after a trial a jury determined that Pacific had breached their implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing – meaning they had not treated Steele fairly throughout the process, and thus inflicted emotional harm and economic damages for loss of future income.

The jury decided that Pacific owed Steele $3.975 million in damages, an amount that could be reduced if Steele and Pacific reached a settlement.

This is one of the largest jury awards a falsely accused student has ever received.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)