In the pre-dawn gray of October 24, 1944, Adm. Kurita Takeo stood on the bridge of the super battleship Yamato and watched impassively as the convoy he was leading slipped into the Sibuyan Sea. He was lucky to be alive. Just a few hours before he’d been on the bridge of his own flagship, the cruiser Atago, when it was practically blown out from under him by Darter’s well-aimed spread of torpedoes. But, other than being drenched and losing a pair of very expensive shoes, and no doubt some jittered nerves, the admiral was no worse for wear. Even reduced in strength by the sinking of the cruisers Atago and Maya, and the retreating Takao with two destroyers assigned to escort her home, he still had under his command a mighty surface fleet, which included five battleships.

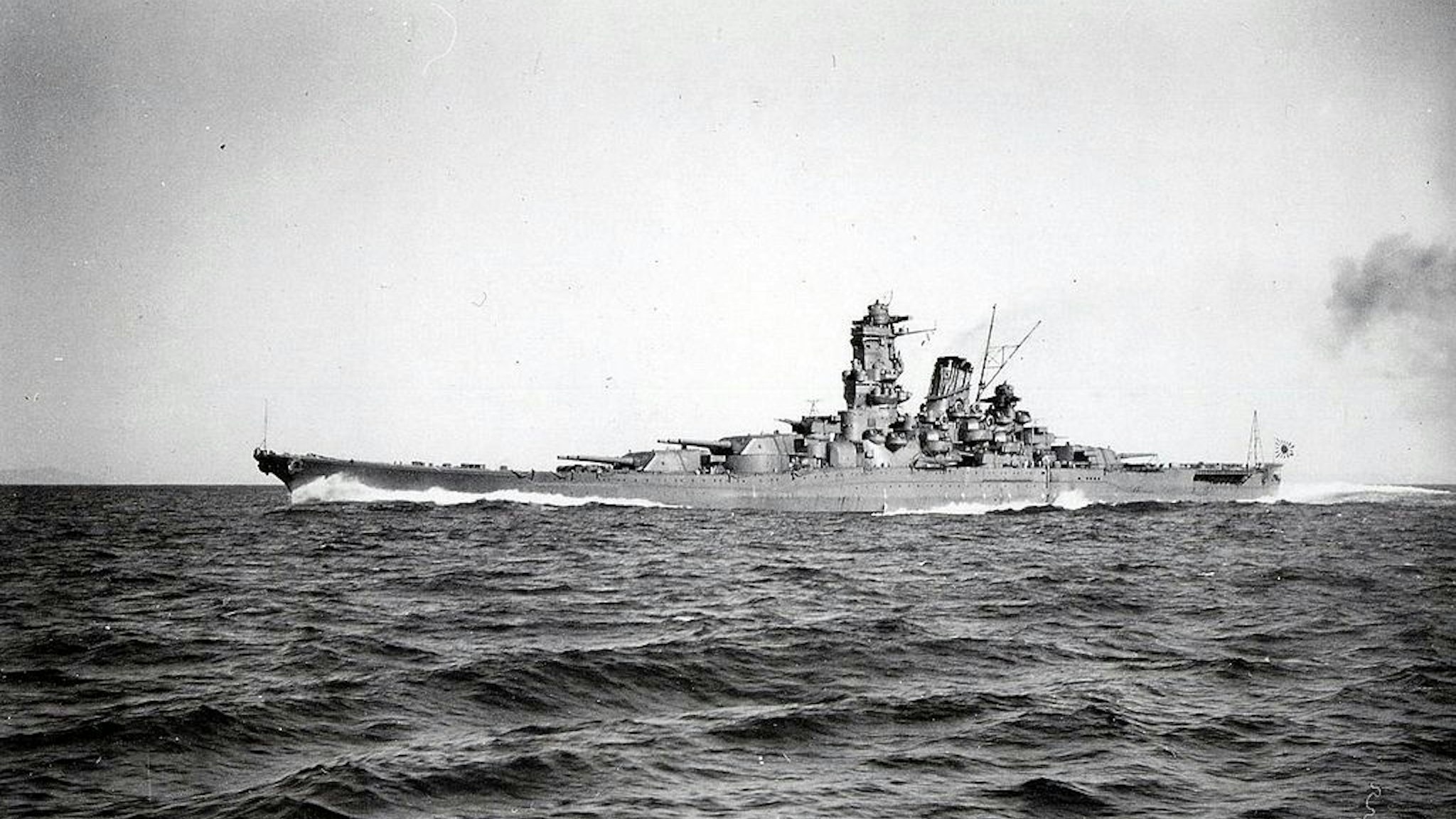

Among these were the gargantuan Yamato from which he now commanded and her sister ship Musashi sailing a mile off her starboard beam. These vessels when fully loaded as they were now displaced an astonishing 72,000 tons and carried nine 18.1-inch main guns capable of firing a one-ton shell 25 miles, making them the most powerful battleships ever produced.

A man with a fondness for Johnny Walker Black scotch (a taste he’d learned from his mentor, the legendary Adm. Yamamoto Isoruku, now dead), Kurita was a brave and approachable seaman who valued his men’s lives and was universally beloved by them in return. History would remember him after this action as hopelessly timid, but that would not be a fair verdict. His courage was undisputed. The historian John Prados offers that over the course of the war Kurita had been “bombed, shelled, torpedoed and generally harassed more than almost any other Japanese commander…because he kept putting himself in harm’s way.” He was picked to lead Center Force, the largest contingent of the Sho-Go’snaval attack, for a reason. Unfortunately for Kurita, as if to add truth to Prados’ observation, his ordeal at the hands of the Americans was just beginning.

After the Darter/Dace attacks, other U.S. submarines had homed in on Center Force and were now tracking it like pilot fish, sending a barrage of dispatches to Halsey and Kinkaid via Australian relay. Subs Bream, Angler, and Gitaro reported the make-up of the enemy force, its course and speed. The aggressive submarines attacked and Breamtorpedoed and damaged the cruiser Aoba. It was clear that a large Japanese battle column was rounding the southern tip of Mindoro and entering the Sibuyan Sea.

Adm. Halsey was nicknamed “Bull” for a reason. He relished combat with the enemy. MacArthur would fondly write of Halsey: “He was of the same aggressive type as John Paul Jones, David Farragut, and George Dewey. His one thought was to close with the enemy and fight him to the death. The bugaboo of many sailors, the fear of losing ships, was completely alien to his conception of sea action.” Up until then, Halsey had the four task groups of Task Force 38 more or less rotating their coverage of Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, which was busy conducting the landings and providing shore bombardment. Now he ordered them all to steam west toward the Philippines and sent out scout aircraft with an aim to attack this new threat.

At 0746 on the morning of October 24, a Helldiver bomber from the U.S. carrier Intrepid made a visual on Kurita’s fleet and from 9,000 feet sent out an alert. The scout reported eyes on five battleships, nine cruisers and 13 destroyers. The signal sent a shudder through the Task Force 38 as this report indicated that the biggest Japanese surface fleet ever seen was headed for Leyte. Halsey moved in to meet an obviously determined foe.

When at 0900 the enemy armada was in range, Halsey turned his carriers into the wind and gave the order to launch aircraft. Adm. Kurita’s already harrowing experience was about to get a lot worse.

At 1018, aboard Center Force’s screening destroyer escorts, the sharp-eyed look-outs with powerful binoculars spotted the first incoming wave of American attack planes from a distance of 25 miles and alerted Kurita on board Yamato. This was two full strike packages from Cabot and Intrepid, each consisting of 12 Avenger torpedo planes, 12 Helldiver dive-bombers, and 20 escorting Hellcats. Kurita signaled to his command: “Enemy attackers are approaching. Trust in the gods and do your best.” Throughout the long day, beginning at 1030, four successive waves of American aircraftfrom five different fleet carriers and one light carrier screamed in from the east to punish Kurita’s exposed warships with torpedoes, bombs, and strafing runs.

At the same time Halsey’s fliers were winging toward Kurita’s ships in the Sibuyan Sea, on Luzon Vice Adm. Onishi Takijiro directed three waves of land-based aircraft from his First Air Fleet against Task Force 38 in flights of 50 at a time. The CAP Hellcats pounced on them well away from the main body and knocked them down in droves. A steel curtain of anti-aircraft fire sent whizzing tracers crisscrossing the sky as a patchwork of black clouds from heavier guns with proximity fused shells lashed at the surviving Japanese aircraft.

Although most never got close to scoring a hit, one Judy dive bomber was successful in landing a 550-pound bomb squarely on the light carrier Princeton and her deck was soon engulfed in flames. With most of Princeton’s crew save damage control off the ship, the light cruiser Birmingham slid alongside her to direct firefighting. Suddenly a colossal explosion rocked the stricken carrier, sending a storm of deadly fragments into the crowded deck of the cruiser. Birmingham’s captain would describe the horrific scene on the main deck as “a veritable charnel house of dead, dying, and wounded.” 229 men were killed to add to the Princeton’s 100 lost, and twice as many were wounded. It was the most successful Japanese attack of the day.

While the Princeton east of Luzon was succumbing to her wounds, back on the other side of the big island in the Sibuyan Sea, Center Force was enduring one attack after another numbering over 250 bombing sorties. American pilots noticed the torrent of anti-aircraft and marveled at the many colored ordinance used by Japanese gunners to help them identify their rounds. But with practically no fighter cover to protect them, the lumbering warships were easy prey and only 12 U.S. aircraft would be lost. By early afternoon a frustrated Kurita was frantically radioing to ascertain what had become of both Ozawa’s decoy force and Onishi’s land-based fighter protection on Luzon—the latter of whom had chosen to throw his planes against the buzz saw of Task Force 38’s CAP and anti-aircraft guns with nothing to show other than one light carrier sunk and light cruiser heavily damaged.

Of the many Center Force targets at their disposal, the American fliers repeatedly dove down on the big Musashi. Flying through curtains of anti-aircraft fire, which included special star shells fired from the battleship’s main 18.1-inch batteries at a distance of 10 miles, the unrelenting Helldivers and Avengers hit the massive vessel with an estimated 17 bombs and 19 torpedoes respectively. This was too much even for a warship deemed “unsinkable” to withstand; damaged beyond hope and taking in tons of water, Kurita was forced to leave her behind to her fate.

At 1936 that evening Musashi would capsize and sink, taking with her over 1,000 of her 2,300-man crew, as well as many luckless survivors of the sunken Maya that had been transferred to the big battleship. Her wounded vice admiral in command, Inoguchi Toshihei, would write down his thoughts to be forwarded to Toyoda and hand the notebook to his executive officer Capt. Kenkichi Kato. The note was a confession that he regretted placing too much faith in battleships and big guns in this modern air age. He also placed Kenkichi in charge of getting survivors safely off his foundering vessel. Inoguchi then disappeared into his cabin to go down with the ship.

To get his force clear of harm’s way until nightfall, Kurita ordered the remainder of Center Force to reverse course and sail west until out of range of the American aircraft. They would turn back east again during the night where they could approach the San Bernardino Strait unmolested. The Sibuyan Sea action, the second phase of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, was over at sunset. However, Kurita’s turn-around to the west would have important consequences. American fliers, like their Japanese counterparts, could be prone to exaggeration as well. Although they’d definitely bloodied the enemy nose, having scored hits on the battleships Yamato, Nagato, and the cruiser Myoko which was compelled to withdraw from the column, and indeed sent one of her most feared battlewagons, Musashi, to the abyss, they’d by no means destroyed Center Force.

Yet Halsey’s fliers reported they’d effectively crippled the Japanese fleet, falsely claiming three additional cruisers and a destroyer sunk and the other battleships damaged. Therefore, news of the enemy’s retiring to the west was misread as a retreat. It was a dangerous misapprehension indeed.

Brad Schaeffer is the author of the acclaimed World War II novel Of Another Time And Place.