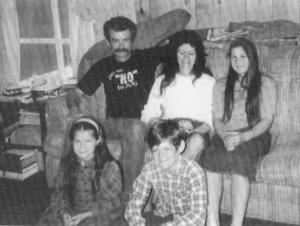

Randy Weaver was a former Army Green Beret who, in the late ’70s, worked in an Iowa factory, providing for his wife, Vicki, and their children. A devout religious family, the Weavers decided to leave Iowa and move to Ruby Ridge in Idaho, just 50 miles from the Canadian border, believing the apocalypse was coming. They built a small cabin on the top of the mountain and lived there for years with little incident.

In 1984, however, a dispute with a neighbor ended with the neighbor being ordered to pay Weaver $2,100. Furious, this neighbor wrote letters to the FBI, Secret Service, and county sheriff claiming Weaver had threatened to kill the pope, President Ronald Reagan, and the Idaho governor.

Charges were never filed, but the investigation led to questions about Weaver’s association with the neo-Nazi group known as Aryan Nations. While Weaver and his family had attended some of their meetings socially, he was never a member.

Wikicommons

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) used this connection to entrap Weaver. A confidential ATF informant attended the World Aryan Congress, his first time attending. He had been invited by Frank Kumnick, a known associate of Aryan Nations and a previous ATF target. While at this Congress, the ATF informant started talking to Weaver, and the two would continue to meet several times.

In October 1989, the informant claimed Weaver had sold him two sawed-off shotguns – a federal crime. It is widely believed that Weaver was not a man regularly altering shotguns and selling them, but that he had been coerced into doing so by the ATF informant.

The ATF informant’s handler, Herb Byerly, in June 1990 used the weapon charge as leverage to force Weaver to act as his new informant. Weaver refused to be a “snitch” and was charged for the sawed-off shotguns. The ATF also claimed that Weaver had several criminal convictions and had robbed banks, claims that were later determined to be false by a 1995 Senate investigation into the events of August 1992.

In December 1990, a federal grand jury indicted Weaver for making and possessing illegal firearms. He was not indicted for selling those firearms.

Based on its own false claims, the ATF decided it was too dangerous to arrest Weaver at his home, so they once again tricked him. Agents posing as motorists who had broken down on the side of the road arrested Weaver when he and his wife stopped to help them, putting them face down in the snow. Weaver was released on bail and told his trial would begin on February 19, 1991. Through court maneuvering, the start date moved and Weaver became confused. Weaver didn’t show up, but believing he may have thought the trial date was moved to March 20, the United States Marshals Service (USMS), agreed to wait until after that day before arresting Weaver for failure to appear in court. On March 14, however, the U.S. Attorney’s Office called a grand jury to indict Weaver for not appearing.

Once the case was in the U.S. Marshal’s hands – as Weaver was now considered a fugitive – they were not informed that the ATF had attempted to make Weaver an informant.

Believing that he would not receive a fair trial based on everything that had happened so far, Weaver refused to appear for his trial. At one point, his defense attorney erroneously told him that if he lost at trial he would lose his land, leaving his wife homeless, and the government would take his children.

Weaver’s distrust in the government grew exponentially after this, and he refused to surrender when U.S. Marshals attempted to contact him. Over the next year, U.S. Marshals made numerous attempts to negotiate Weaver’s surrender, using third parties and posing as potential property buyers.

During this time, the Marshals also developed a Threat Source Profile on Weaver that painted him as an anti-government radical who was armed and dangerous. It included a psychological profile completed by someone who had never met Weaver and knew so little about the case that he called him “Mr. Randall.”

Beginning in March of 1992, U.S. Marshals sent surveillance teams to set up cameras around the Weaver’s property to record their activity. Marshals saw that Weaver and his family would take up armed positions whenever a vehicle or visitor arrived on their property – but would lower their weapons once they recognized the person.

On April 18, 1992, a helicopter flew over Weaver’s property after being hired by Geraldo Rivera’s news program at the time, “Now It Can Be Told.” U.S. Marshals claimed they received reports that Weaver shot at the helicopter, but the Marshals’ own surveillance team on the property that day reported no shots. Weaver also denied the reports, and the helicopter pilot told the FBI that Weaver didn’t shoot at his helicopter. But U.S. Marshals and the FBI used these false claims as justification for the rules of engagement it would follow when moving onto Weaver’s property to arrest him.

Govt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Three months later, after Henry E. Hudson was confirmed as the new head of USMS, six Marshals went to Weaver’s property on August 21, 1992, to scout out places where Weaver could be arrested away from his cabin. The team, dressed in military camouflage and carrying M16 rifles, at one point threw some rocks to test Weaver’s dog’s reaction. The dogs barked, and Weaver’s friend Kevin Harris, as well as Weaver’s 14-year-old son Sammy, followed the dogs to investigate. Weaver took a different route to follow the dogs, all hoping the dogs had found some deer.

At this point, the stories diverge. Weaver and Harris claimed that Harris and Sammy found the heavily armed Marshals, and that their dog, Striker, started barking at the Marshals. The Marshals shot and killed Striker. Sammy then allegedly fired a shot near the Marshals and yelled at them about killing his dog, which prompted the Marshals to begin shooting. Sammy tried to run up the nearby hill and was shot in the back by U.S. Marshal Larry Cooper. He died instantly.

The U.S. Marshals claimed that they gave the Weaver a surrender order and that Harris began firing at them, so they fired back and ended up killing Sammy and Striker. At this time, Harris shot U.S. Marshal William Degan in the chest and killed him.

Weaver and Harris returned to the cabin and told Weaver’s wife Vicki what happened. She and Weaver reportedly went out to get Sammy’s body and bring him back into the cabin, with the family grieving his death. They had to put his body in a shed near the main cabin because they couldn’t leave the property.

Now the Marshals, ATF, and the FBI were involved, with agents sent to the Weavers’ property. Ten FBI snipers were dispatched to surround the property, and the FBI and Marshal Service approved a special rules of engagement draft that allowed agents to use deadly force if any adult on the property is seen with a weapon after they had been told to fire. The draft also said any dog on the property could be shot if any agent is “compromised” by the dog. The draft also noted that if anyone on the property presented the threat of death or grievous bodily harm other than Weaver, Harris, or Vicki, then the FBI’s rules of deadly force would apply meaning they could be killed in order to prevent death or grievous bodily injury to someone else.

Further, agents could kill any “adult male” if they were seen with a weapon and if the shot would not endanger Weaver’s children.

Hundreds of federal agents converge on Ruby Ridge during the standoff in August 1992. (File / The Spokesman-Review)

For 11 days a standoff ensued. On August 22, before negotiators arrived, FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi opened fire at the Weavers. He shot Weaver in the back while he was lifting the latch on the shed to visit Sam’s body. The bullet exited Weaver’s right armpit. Horiuchi later testified that he had been aiming for Weaver’s spine, but that Weaver moved at the last second.

Weaver had been out with his 16-year-old daughter Sara and Harris when the shot was fired. They ran back to the cabin, and Horiuchi fired another shot, this time striking Harris in the chest. This bullet also killed Vicki Weaver, who had been standing at the cabin door when Harris entered. She was holding her 10-month-old baby Elisheba.

In “American Experience: Ruby Ridge,” a documentary that aired on PBS in 2020, Sara Weaver described the moment her mother was murdered.

“And I felt things hit my face, and Mom dropped next to me,” Sara said, her voice breaking as she held back tears. “It took me a second to comprehend that mom had just died and that it was parts of her that had hit my face.”

Weaver picked up the baby and gave her to one of his other daughters so that he could help pull Vicki’s body into the cabin.

“We were being hunted, that’s how it felt,” Sara added.

Horiuchi was charged with manslaughter for the killing of Vicki, but the charges were later dismissed despite so many people witnessing the shooting.

In the early days of the siege, media outlets were only able to receive information from government sources, so their coverage was skewed as a white supremacist shooting federal agents. The narrative began to shift when the FBI told reporters it had found 14-year-old Sammy Weaver’s body.

Hostage negotiators didn’t know that Vicki had died until days later, so they kept directing their negotiations toward her, believing she would be the one to talk Weaver into surrendering.

Inside the Weaver household, with Vicki lying dead on the floor, the family believed the government was taunting them when it continued to speak to Vicki. Sara said her father wanted to yell at the negotiators for doing this, but she stopped him because she truly believed agents would shoot her father if he went near a window.

“They had proven that they were there to shoot us,” Sara said.

With no solution in sight, and the FBI finally realizing that the intelligence they had been given about Weaver was inaccurate, they called in James Gordon “Bo” Gritz, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces officer who was known to associate with Right-wing militia groups, to talk to Weaver.

After Gritz’s first discussion with the Weavers, he returned to the FBI agents and told them they had really messed things up and that Vicki was dead and Weaver and Harris were wounded. Eventually, Gritz convinced Weaver to send Harris out so that he could get medical attention, and brought a body bag to remove Vicki’s body from the cabin. As Sara Weaver described, the entire family grieved as they took Vicki away.

Weaver became adamant that he and his daughters would not leave the cabin due to the deaths of Sammy and Vicki, but Gritz refused to leave as well, and was eventually able to get Weaver to leave the cabin with his daughters.

Sara said she fully expected to die when they left the cabin, believing she and her sisters would be shot by government agents. When they left, they passed the military encampment that had been set up to handle the Weaver situation, saying it “made no sense” to have such a large presence for their little family.

Weaver and Harris were charged with numerous offenses, with Harris being charged with first-degree murder for the death of U.S. Marshal Bill Degan. Both were acquitted on all charges, except Weaver was found guilty of the original charge for missing his court date and violating his bail conditions. He spent 16 months in prison and was fined $10,000.

In 1995, the Government Accountability Office and the U.S. Senate investigated the siege on the Weavers and presented a report that found numerous errors by law enforcement, including deeming the rules of engagement to be unconstitutional.

Weaver and his daughters sued the federal government for the wrongful death of his wife and 14-year-old son. In August 1995, Weaver settled for $100,000 and each of his three daughters received $1 million. They had asked for $200 million.

Randy Weaver died on May 11, 2022, at the age of 74, just shy of the 30-year anniversary of the siege.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)