The following is an exclusive excerpt from Rigged: How the Media, Big Tech, and the Democrats Seized Our Elections by Mollie Hemingway, available October 12 from Regnery Publishing.

The Pennsylvania Trump team had previously decided to sue in federal court on the issue of how ballots were being treated differently in different areas of the state, filing in the Middle District of Pennsylvania. Since ballots across the state were counted according to dramatically different legal protocols, the case alleged, the state had violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment mandating uniform legal treatment for Americans. It was the same argument that had merit in Bush v. Gore, the federal case that determined who would be the forty-third president of the United States.

Kerns, with the help of powerhouse law firm Porter Wright, filed the case. The judge set a tight and aggressive schedule. Briefs were due later that week, and the hearing was scheduled for the following Tuesday.

The Lincoln Project, a Democratic political action committee that bills itself as a group of former Republicans, had learned of the lawsuit and began a campaign of personal destruction against the lawyers working the case. They published the names of Ron Hicks and Carolyn McGee, two attorneys with Porter Wright, the Pittsburgh law firm working to protect Pennsylvania voters.

“Here are two attorneys attempting to help Trump overturn the will of the Pennsylvanian people,” a tweet from the group said, identifying them by name and photo. “Make them famous.” Within minutes, the law firm was being deluged with vulgar and vicious attacks as well as death threats.

Any attorney working on the case was being verbally assaulted. Kerns was repeatedly called a “cunt,” a “fucking bitch,” a “traitor,” “stupid,” “treacherous,” a “fucking Nazi,” and a “whore.” Some expressed hope that she would lose her possessions, her law license, and her life. “We know where you live, where your office is, and where your court dates will be. Thousands of us will wait for you outside, licking our chops. You and your partners on this case are scumbag pieces of shit, and I’d love for nothing more than to see you begging for your life,” wrote one emailer. “The people will rise, the mobs will ascend on you and your colleagues, and you will die a painful, scary death. This country knows how to deal with treason.” In addition to threats such as this, two explicit death threats brought the attention of the FBI.

It was one thing to have to field threats and attacks from random supporters of Democrats—that was almost to be expected in highly politicized litigation such as this. But one of the harassing phone calls came from an attorney in the Washington, D.C., office of Kirkland & Ellis, the outside counsel to Boockvar. The code of professional conduct for legal practitioners in the Middle District of Pennsylvania includes a commitment to “treat with civility and respect the lawyers, clients, opposing parties, the court and all the officials with whom I work.”

When Kirkland & Ellis was notified of the voicemail attack, the firm at first suggested it might not have been from one of its attorneys. Later, the firm admitted it had come from one of its attorneys, even if he was not working on that particular election lawsuit, and acknowledged that it was “discourteous and not appropriate.” Kerns asked the judge to sanction the firm for the shocking behavior of one of its lawyers. “It is sad that we currently reside in a world where abuse and harassment are the costs of taking on a representation unpopular with some. It is sanctionable when that abuse and harassment comes from an elite law firm representing the Secretary of State,” she told the judge. On Thursday, Porter Wright withdrew from the case. The threats from Democratic mobs were endangering the firm and its clients. Kerns was now the only public face representing the Trump campaign in the lawsuit. The briefs were due the next day.

In Porter Wright’s absence, the Trump campaign brought on respected Texas attorneys John Scott and Douglas Bryan Hughes. Helping with the briefs were a slew of former Supreme Court clerks, avoiding leftist mobs by working behind the scenes to get the case through its hearings. It was the best shot the Trump campaign had, and the facts of the case were in their favor.

The Texas attorneys entered into the case. To practice law in a state, attorneys have to be admitted to the bar. If they haven’t been admitted but desire to participate in a particular case, they can be allowed to participate pro hac vice, Latin for “for this occasion.” The attorney who requests the authorization has to request permission from the court, and usually gets the main local attorney on the case to sponsor his or her participation. Kerns had no problem agreeing to sponsor the Texas attorneys, and they granted her request to admit them.

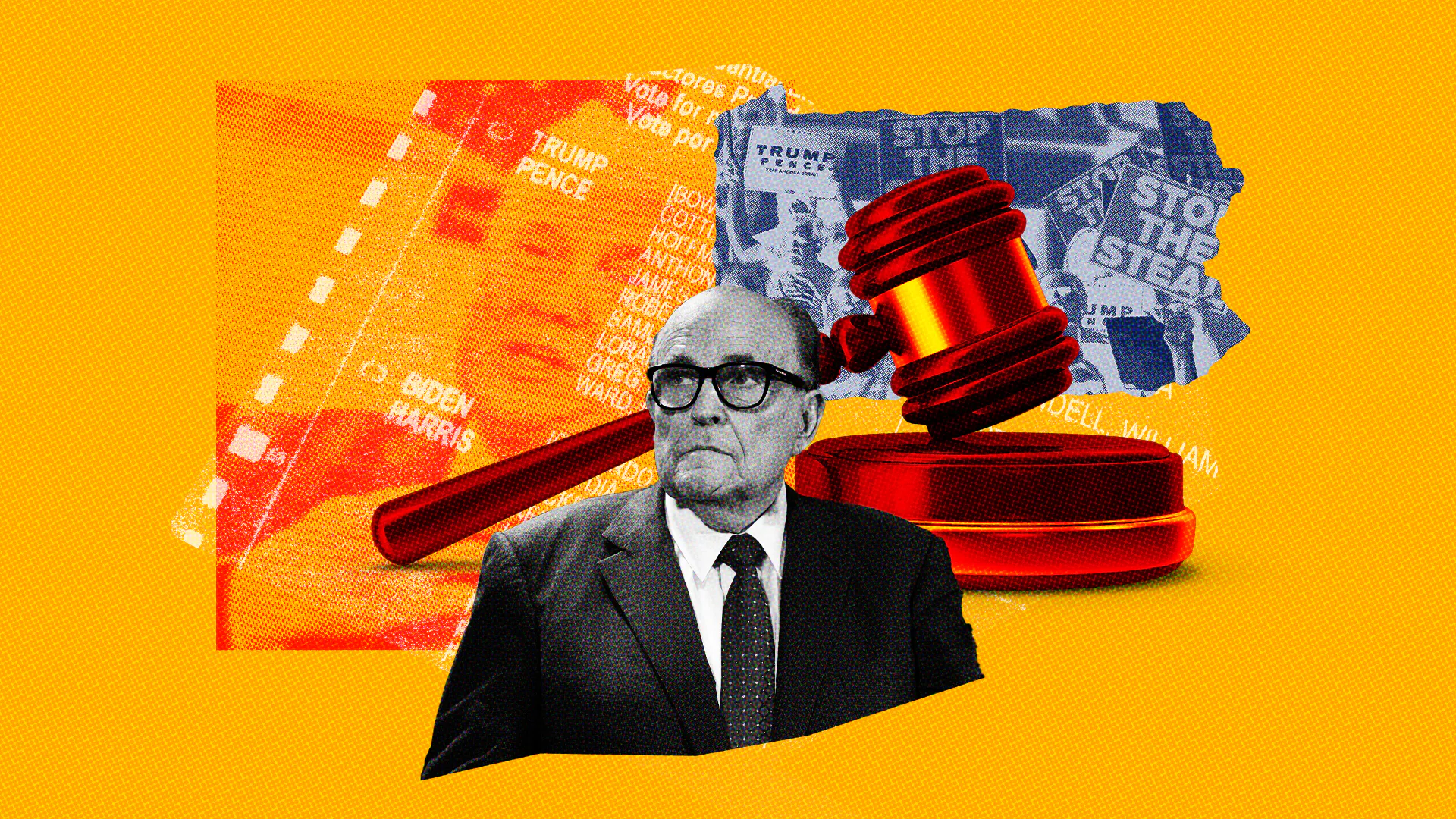

Prior to this case’s being heard, Rudy Giuliani had held a press conference at the Four Seasons Total Landscaping company, where instead of talking about all of the legitimate issues affecting the Pennsylvania election—and there were so many—he put forth dramatic claims about voter fraud. The first person he brought up as a witness to irregularities was a man named Daryl Brooks, who said he was a paid GOP poll watcher. “They did not allow us to see anything. Was it corrupt or not? But give us an opportunity as poll watchers to view all the documents—all of the ballots,” said Brooks.

But in addition to being a convicted sex offender with strong Democratic Party ties, Brooks was well known as a perennial candidate in New Jersey. He was not an ideal witness, to put it mildly.

The veteran Republican lawyers were at best confused by Giuliani’s approach and at worst completely opposed to it. Giuliani called Kerns and told her he was taking over her Pennsylvania litigation. She didn’t agree with the direction he wanted to take the federal case, and so she was not willing to sponsor his participation, as she had done for the Texas lawyers. It wouldn’t matter: Giuliani found another attorney to help him enter into the case, and he took it over that way.

Kerns filed a petition to withdraw, as did the two Texas attorneys. While the Texas attorneys were allowed out of the case, Kerns was not permitted out. Because of the departure of the Porter Wright attorneys, the judge was adamant that at least one attorney should stick with the case all the way. “I believed it best to have some semblance of consistency in counsel ahead of the oral argument,” Judge Matthew Brann wrote, denying her request.

The threats against Trump attorneys were out of control at this point. Out of fear for her safety, Kerns was brought through the back door of the courthouse by U.S. Marshals.

The hearing went on for hours, with Giuliani talking about fraud that he could not substantiate with evidence. The judge asked Kerns to speak, and she noted that no one was talking about equal protection, the original complaint the campaign had filed. Courts look extremely unkindly on attorneys who fail to stick with the arguments in the original complaints. Kerns asked again to be let out of a case that was running off the rails. Giuliani asked her to stay. She called the judge the next day and asked to be let out and was finally allowed off the case. The judge quickly approved the defendant’s motion to dismiss in a blistering opinion saying Giuliani had presented the court with “strained legal arguments without merit and speculative accusations.”

The Obama-appointed judge had been open to the case and its legal arguments at the beginning, but showed little tolerance for what it had become.

Giuliani regularly downplayed very real issues with the 2020 election in Pennsylvania by emphasizing less relevant—and less actionable—claims. For instance, the Public Interest Legal Foundation had sued Pennsylvania over the twenty-one thousand dead people that were on its voter rolls.

The group’s data, which it filed under seal with the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, showed thousands of dead people on the voter rolls, some of them for many years. It said that hundreds of them had shown up as voters in 2016 or 2018.

“AT LEAST 21K Dead People on Pennsylvania Voter Rolls ‘9,212 registrants have been dead for at least five years, at least 1,990 registrants have been dead for at least ten years, and at least 197 registrants have been dead for at least twenty years,’” Giuliani tweeted on November 6.

Media coverage of the tweet and the issue of dead people being on voter rolls was predictably awful. “No, 21,000 Dead People in Pennsylvania Did Not Vote,” was the New York Times headline on November 6, although no one had actually made that claim. The claim was that dead people’s names remained on Pennsylvania voter rolls years after they had died, which increased opportunities for fraud. The Times dismissed the legitimacy of the case, saying the judge overseeing it was doubtful” of it. News organizations purported to check the fact of whether Pennsylvania had dead people on its rolls. Snopes rated it “false,” while FactCheck.org said it had “thin” evidence.

The Public Interest Legal Foundation had asked a judge before the election for an injunction to stop any of the dead people listed on voter rolls from voting, but it wasn’t granted. However, less than five months after the November election, Pennsylvania settled with the Public Interest Legal Foundation and agreed to remove the dead voters on its list before the 2021 municipal elections.

Still, the focus on the relatively marginal issue of dead people on the voter rolls was far less pertinent than the issue that Kerns and the previous legal team had raised. Kerns’s suit identified an issue that had affected all 6.1 million Pennsylvania voters. Her suit raised a fundamental legal question, drawing attention to the problems caused when law-abiding voters are treated differently than non-law-abiding voters depending on where they live in a state. That issue potentially affected the actual outcome of the 2020 race in a way that the dead voter roll issue wouldn’t and couldn’t.

For perspective, the initial Republican legal strategy was to keep the margin of Biden’s lead relative to total ballots cast down to .5 percent, the threshold that would trigger an automatic recount. As votes kept being located and counted, Biden would eventually be certified the victor by more than eighty thousand votes, yielding Biden 1.2 percent more of the vote than Trump—more than twice what he needed to prevent a recount.

By wasting time on less relevant claims, an important lawsuit failed. It had catastrophic effects for the remaining legal battles. Pennsylvania could have been the first domino to fall for the Trump campaign in a sequence of tightly contested courtroom victories. Instead, it was the beginning of the end for the campaign’s effort to hold Democrats accountable for foul play. It also had a ripple effect throughout the legal community. The media were soon dismissing all legal challenges as baseless attempts to prove widespread fraud, ignoring more substantive claims. The avalanche of bad publicity scared off credible lawyers from participating in further election challenges on behalf of the Trump campaign, and it made judges inclined to view any such challenges, no matter how merited, with suspicion.

Mollie Hemingway is an editor, commentator, Fox News contributor, and best-selling author of Justice on Trial: The Kavanaugh Confirmation and the Future of the Supreme Court. Her newest book, Rigged: How the Media, Big Tech, and the Democrats Seized Our Elections, is available October 12 from Regnery Publishing.

The views expressed in this opinion piece are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?

.png)

.png)