Franklin Roosevelt was a patient man, and he would need all he could muster this July day in 1944 to deal with the man who’d made the President of the United States wait for him and Admiral Chester Nimitz and his naval entourage on board the cruiser Baltimore freshly docked in Pearl Harbor. Only General Douglas MacArthur, whose plane had landed earlier following an arduous flight from Brisbane, Australia, would have the impertinence to arrive in a limousine with sirens wailing.

That was MacArthur’s way. Like his boss, he understood the value of image. In MacArthur’s case he wanted to give the impression of having been pulled from the front—which he had been—by wearing a leather flying jacket. But the general was not only a gifted strategist who in the two years since his campaign that began in Australia in March 1942 had taken more territory with less loss of life than any other top commander in any theater, he was a war hero, beloved by the American people back home. The politically astute Roosevelt was currently making a bid for an unprecedented fourth term in office, and he didn’t need a soured MacArthur sowing mischief in the GOP camp. So he let it go. Still, when MacArthur strode up the Baltimore’s gangplank, the president grinned and kidded the general about wearing a leather jacket in Hawaii. MacArthur retorted: “You weren’t where I just was. It’s cold up in the sky.” Then after initial pleasantries and ceremony, the President, MacArthur, and Nimitz agreed to convene the next morning at the home of a Waikiki millionaire. There were urgent matters to attend to.

For two years in the prosecution of the Pacific War an uneasy command structure had been at work; so far it had actually yielded great success despite its cumbersome arrangement. In the southern Pacific, starting from Port Moresby, MacArthur and his U.S. and Australian army command, along with his assigned air and naval contingents, moved up the northern coast of New Guinea and along the way captured the Admiralty Islands, and tamed the Bismark Sea. In the central Pacific, Nimitz with his island-hopping campaign launched from Hawaii, had captured one atoll and archipelago after another, starting in the Solomon Islands and moving relentlessly toward Japan, seizing the Gilberts, the Marshalls, the Carolines, and finally the Marianas. In the process the mutually supportive campaigns had managed to neutralize Japan’s enormous anchorage and bastion of Rabaul on Cape Gloucester, and laid waste to its naval stronghold on Truk. In a series of historic—and violent—naval air and surface engagements which began at the Coral Sea in May 4-8, 1942, and culminated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on June 19-20, 1944, the U.S. and its British Commonwealth allies had handed the Japanese one defeat after another. But now the two commanders had to agree on where to go from here. That’s what this conference would decide. FDR would make the final determination. All egos and politics aside, the decisions made here would mean life or death for thousands of American boys. Roosevelt took his responsibilities deadly seriously.

So where to go next? Nimitz and MacArthur each had different ideas. Nimitz, arguing the case laid out by his boss in Washington D.C., Adm. Earnest J. King, proposed to bypass the Philippine Islands and invade Formosa (Taiwan). His argument was that Taiwan stood astride Japan’s vital sea lanes to the East Indies, without which it would be starved of oil, rubber, and other vital raw materials. It was also a logical springboard for the final offensive against Japan’s home islands.

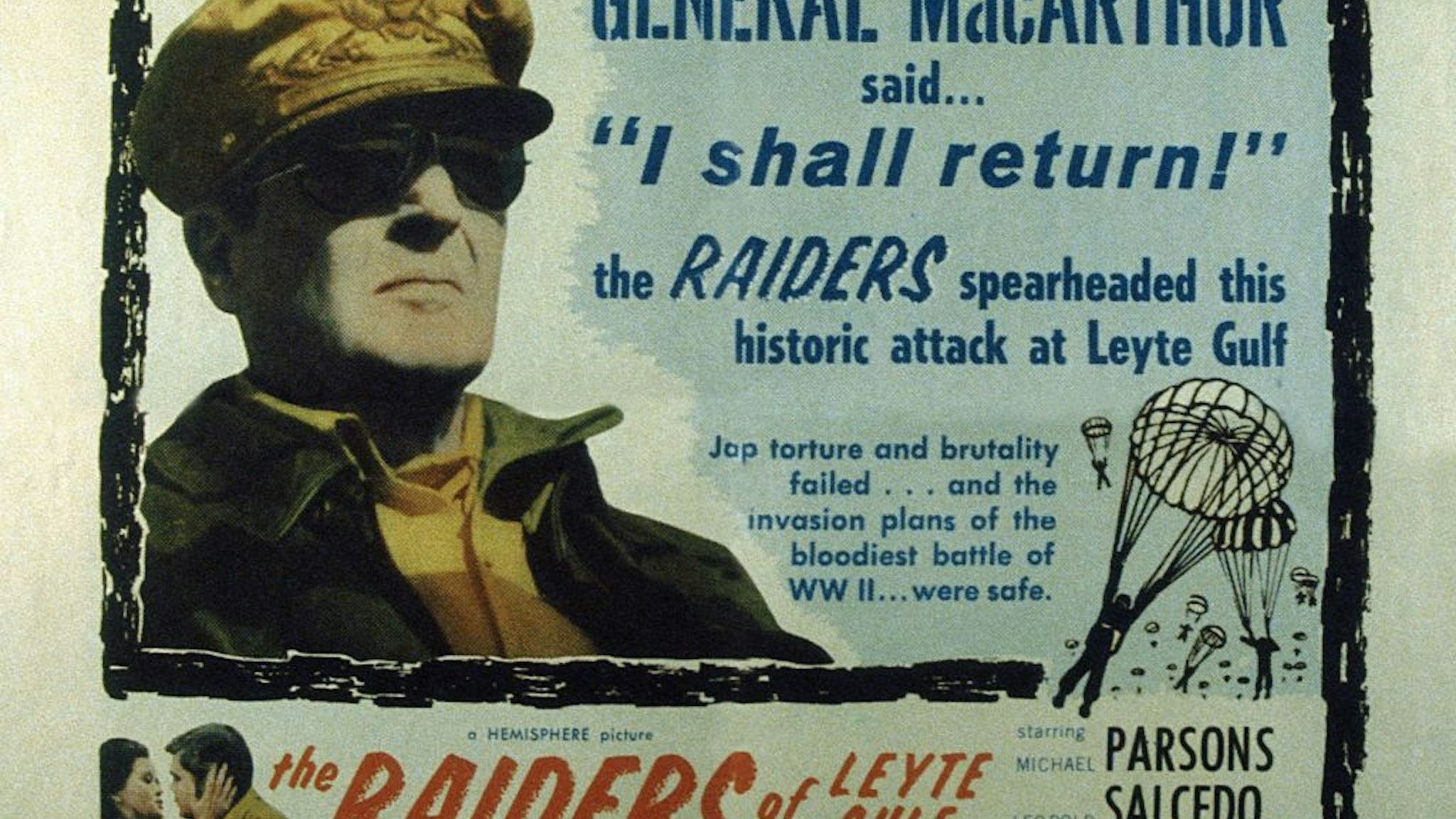

MacArthur disagreed. He argued that the Philippines were the logical next step. “Mindanao, Mr. President,” he said forcefully, tapping a pointer on the giant wall map. “Then Leyte and Luzon.” Roosevelt knew that MacArthur’s reasons were personal as well as anchored in military expediency. Two years earlier, the general promised the Filipinos “I shall return” when he was ordered to leave before America’s island protectorate and its gallant U.S. and Filipino defenders fell to the invading Japanese. To him, this was a sacred vow on behalf of the United States. Also, the men he’d left behind on Bataan and Corregidor Island were languishing in brutal Japanese prison camps. He reminded the President that the Philippine people (and, FDR knew, MacArthur as well) believed the USA had abandoned them to a cruel occupier, and would see bypassing as abandonment yet again. The general insisted the USA had a moral obligation to come to the rescue of those whose islands we’d wrested from the Spanish in 1898. It would not sit well with the voters either, MacArthur coyly reminded the politician among them.

But, in the end, MacArthur’s views were also of a military nature. The archipelago with its airfields, its fine anchorages, friendly populace, and guerilla allies would be an asset, which also could cut off the same sea lanes. Besides (and observers say even Nimitz nodded here) the Philippines, a sprawling mass of large islands located squarely between captured New Guinea and Formosa, and garrisoned by over 300,000 Japanese soldiers, with enemy air and naval forces at the ready, were simply too large to bypass.

Feeling himself persuaded by his top field general’s passion and understanding of the subject matter, Roosevelt asked MacArthur if taking the islands might get bloody. MacArthur assured him, “My losses would be no worse than they have in the past…good commanders do not turn in heavy losses.” It would take some time to convince the DC brass, especially the equally headstrong Adm. King, but eventually it was decided that the Philippines would be the next target. Nimitz, belying MacArthur’s legendary paranoia over a Navy clique trying to shut his army out of the war, pledged his full support and any resources he needed.

Later, as he prepared for his return which had driven him ever forward over the two years, a gratified MacArthur would say to one of his aides while facing the direction of the Philippines, “They’re waiting for me up there. It has been a long time.”

Brad Schaeffer is the author of the acclaimed World War II novel Of Another Time And Place.