On April 15, 1994, Donald Ewing and Doniel Quinn were shot in the afternoon while they sat in a parked car in Kansas City, Kansas.

Police quickly zeroed in on a man named Lamonte McIntyre, who lived just a mile from where the shooting took place. McIntyre had no connection to the victims and no motive to kill them, nor was there any physical evidence tying him to the case. In addition, five people were able to say where McIntyre was before, during, and after the murder.

But police had two witnesses to the shooting who identified McIntyre from a photo line-up, reported the non-profit Centurion, which is dedicated to freeing people who are wrongly convicted. One of the witnesses, Niko Quinn, was a cousin to the victims, and told Assistant District Attorney Terra Morehead ahead of the trial that McIntyre was not the murderer after she first saw him in person. Quinn claimed that Morehead threatened to charge her with contempt and take away her children if she didn’t testify that McIntyre was the man she saw commit the double homicide. Two years after the trial, Quinn recanted her identification in a signed affidavit, saying she had been forced to identify McIntyre as the shooter or risk losing her children. Quinn’s sister also came forward to say she had also witnessed the murder and that McIntyre was not the shooter.

Another witness, Ruby Mitchell, kept changing her description of the gunman and gave contradictory identifications. When she was first interviewed, she said the gunman had slicked back hair and that he was “brown skinned, that’s all I could tell.” Later that day, she told police that she knew the shooter and that his name was Lamonte, whom she knew through her niece. Ruby was taken to the police station to create a composite likeness of the gunman. She was then given five photos to pick out the man she thought was the shooter. These photos included no one with slick backed hair, but did include a photo of Lamonte McIntyre, his brother, his cousin, and two other young black men. As Centurion noted, this photo lineup didn’t include a picture of Lamonte Drain, the man whom Mitchell knew through her niece.

Mitchell’s description of the shooter’s hair changed repeatedly, from slicked back, to “French braids,” which is the style Drain wore at the time, and finally to “short …on the sides and long…on top,” which is how McIntyre styled his hair in the photo used in the lineup. At the trial, Mitchell claimed she hadn’t been “paying attention to hair” during the shooting but was instead focused on the shooter’s face, even though she witnessed the shooting through a screened door more than 100 feet away.

Mitchell later said that detective Roger Golubski, who had driven her to the police station to make the photo identification, had made her feel uncomfortable on the ride. She claimed Golubski had told her she was pretty and that he liked to date black women. She said he asked her if she dated white men. Mitchell said she knew Golubski had a reputation for intimidating black women and exploiting them for sex.

Two other women who witnessed the murder – Josephine Quinn and her daughter Stacy, were not called to testify. Josephine went to the courtroom when McIntyre was on trial to see if she was needed, but was told she was not. She saw McIntyre in court and asked ADA Morehead if he was the accused. When told he was, Josephine said he couldn’t be the shooter because the man she saw had lighter skin, a professional haircut, and was shorter than McIntyre. Josephine later said Morehead dismissed her concerns and said it was up to the jury to decide. Stacy was the one who had the best view of the shooting, yet she was not called to testify.

“She was never even interviewed by the police. Records say that she was ‘not available,’ but she was known to have an ongoing sexual relationship with Detective Golubski,” Centurion reported.

Stacy did testify in 1996 at a post-conviction hearing. There, she described what she saw and said McIntyre couldn’t be the shooter because he was too tall, had different hair, and had bigger lips than the man she saw shoot the victims. The judge dismissed her testimony as not credible.

Stacy reportedly kept talking about the murder, and told her sister – Niko Quinn – that a man named Neil Edgar, who was known as “Monster,” was the real murderer and had been paid by a man named Cecil Brooks to kill Doniel.

In May 2009, Centurion’s founder and investigator Jim McCloskey began looking into McIntyre’s case. McCloskey interviewed witnesses, family members and acquaintances of the victims and McIntyre, as well as alternate suspects and the now-disbarred attorneys who represented McIntyre at his trial. Eventually, McCloskey was able to interview Brooks in prison, where he was serving time after a second-degree murder conviction. Brooks signed an affidavit saying that “Monster” was 15 or 16 at the time of the double homicide and working for Brook’s cousin Aaron Robinson, a drug kingpin in the area. Brooks said that on the night before the murders he, Robinson, “Monster,” and another man discussed Doniel allegedly stealing their drugs. “Monster” was allegedly paid $500 to kill Doniel Quinn and Donald Ewing and told he would receive more money later, but never did.

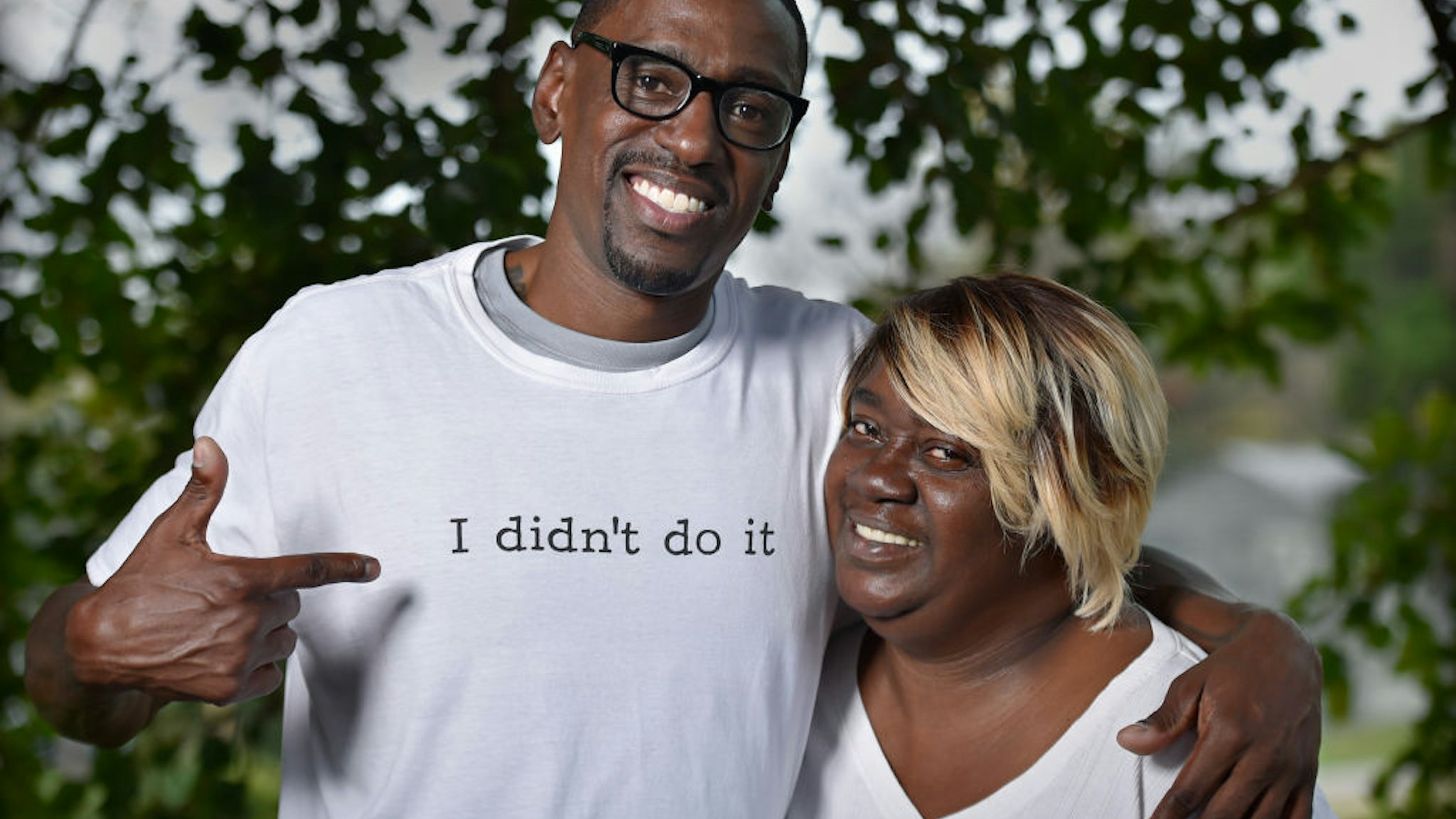

Centurion was able to get the charges dropped against McIntyre and he was released from prison in 2017 after serving 23 years for a crime he didn’t commit. The Washington Examiner reported that in 2018, McIntyre filed a lawsuit against the Unified Government of Wyandotte County and Kansas City, Kansas, for $93 million, alleging they were responsible for the actions of the police officers who put him behind bars.

“The lawsuit specifically names former Kansas City police detective Roger Golubski, who McIntyre says framed him,” the outlet reported. “McIntyre’s mother, Rose, is also seeking $30 million, claiming that Golubski coerced her into sex and framed McIntyre for a 1994 double homicide after she rejected the detective’s later advances.”

Golubski has denied that he abused Rose and dozens of other black women, KCUR reported, and asked that his “alleged bad character” not be allowed as evidence at trial.

“A federal judge on Thursday set a Nov. 7 trial for the civil case. The Unified Government wants to move the trial to Wichita because of the amount of media attention the case has drawn in the Kansas City area,” KCUR reported.